Western Colorado

Culture/Archaeological Heritage

Human history in western Colorado dates back at least 11,000 years. Many groups of peoples have migrated through and settled in what we now call the Western Slope.

The first peoples, known today as Paleoamericans, were skilled hunters who came to the Americas near the end of the Pleistocene period following large game such as mammoths. With the retreat of the glaciers and disappearance of the megafauna, a new culture, today identified as the Archaic, arose where the people adjusted to the changing environment.

A cultural revolution occurred with the coming of agriculture as Native Peoples started cultivating corn as well as beans and squash. By 500 AD, farming had become a fixture in western Colorado which allowed the Ancestral Puebloan and Fremont cultures to grow and develop. A variety of factors including changing environmental conditions forced the people to eventually migrate and their cultures to change. What arose was the hunting and gathering culture of the Ute, who called themselves the Nuche. By 1500 AD, the arrival of the horse dramatically altered the Ute way-of-life allowing them to travel further and faster.

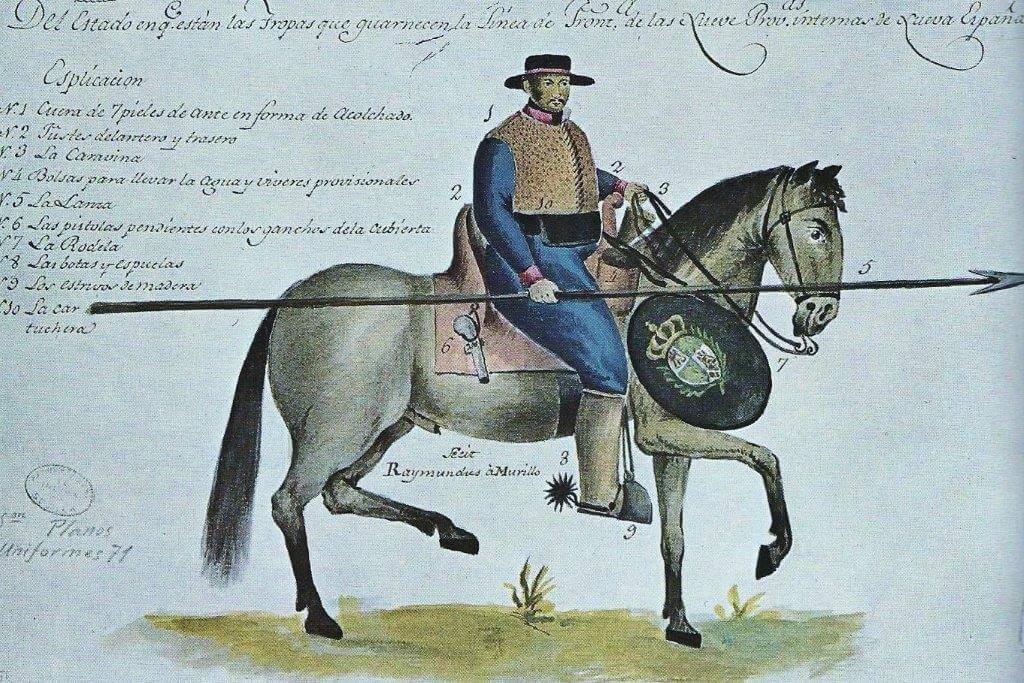

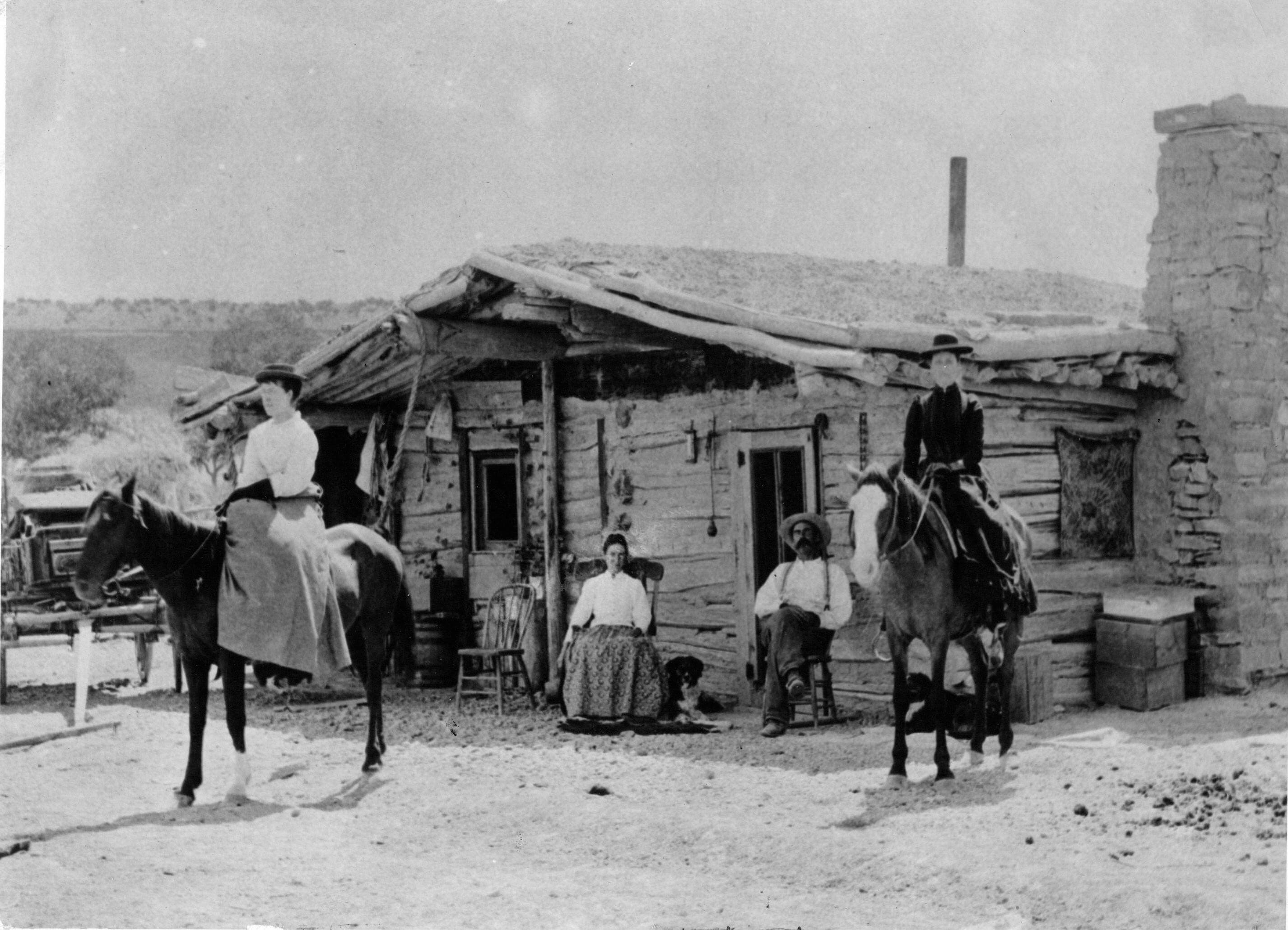

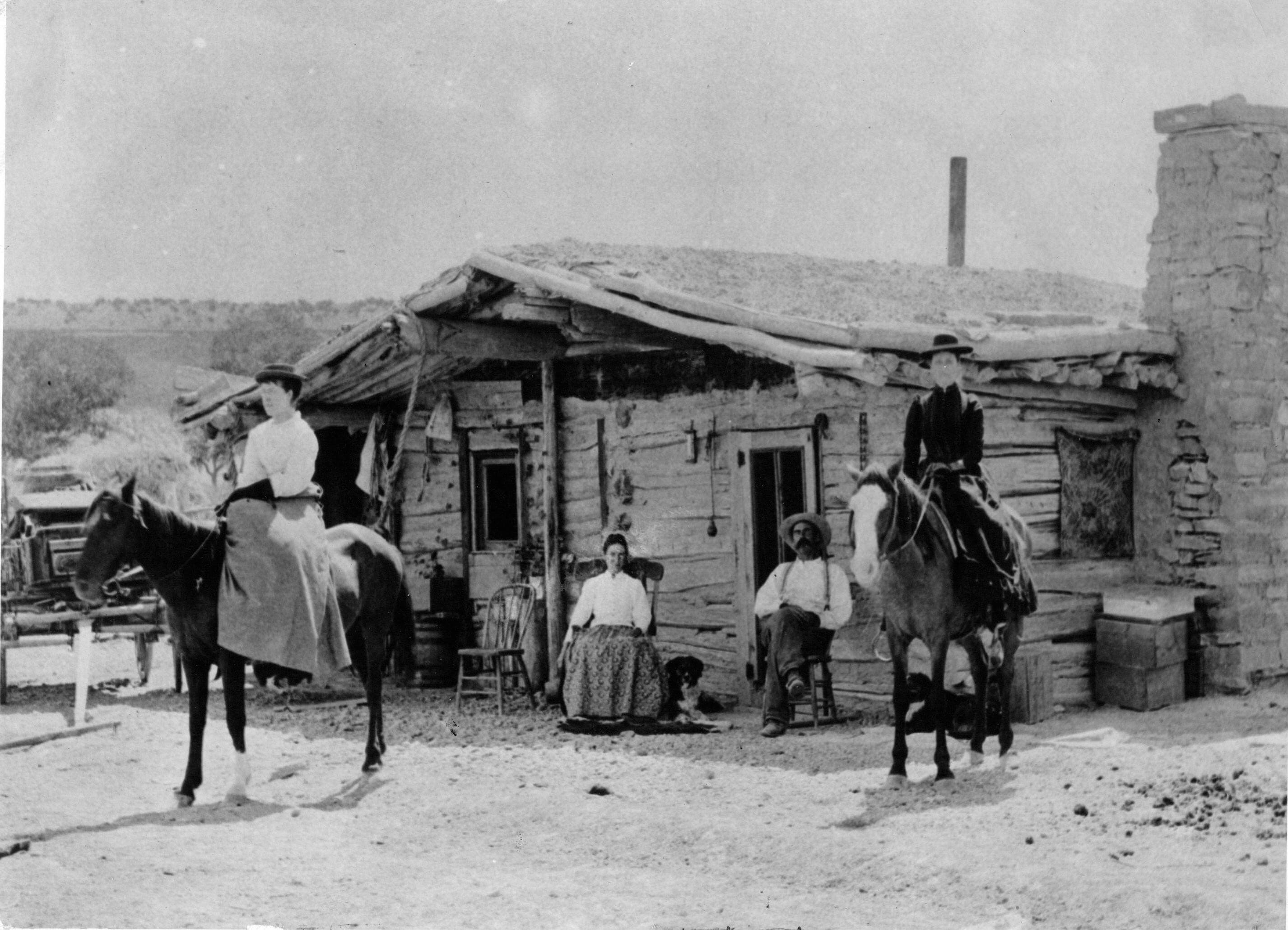

The Ute were soon confronted with the coming of European peoples including explorers, traders, trappers, and miners. This started with the Spanish, but later included citizens of Mexico and the United States. With the expulsion and relocation of the Ute in 1882, settlers came into western Colorado to ranch, farm, mine, homestead, and build communities.

Each of these people have looked at the land a bit differently, but all most likely valued its resources as well as its beauty. Each made their own mark upon the land. Today, evidence of these past and current peoples throughout western Colorado can be found on your Public Land.

Western Colorado Culture/Archaeological Heritage

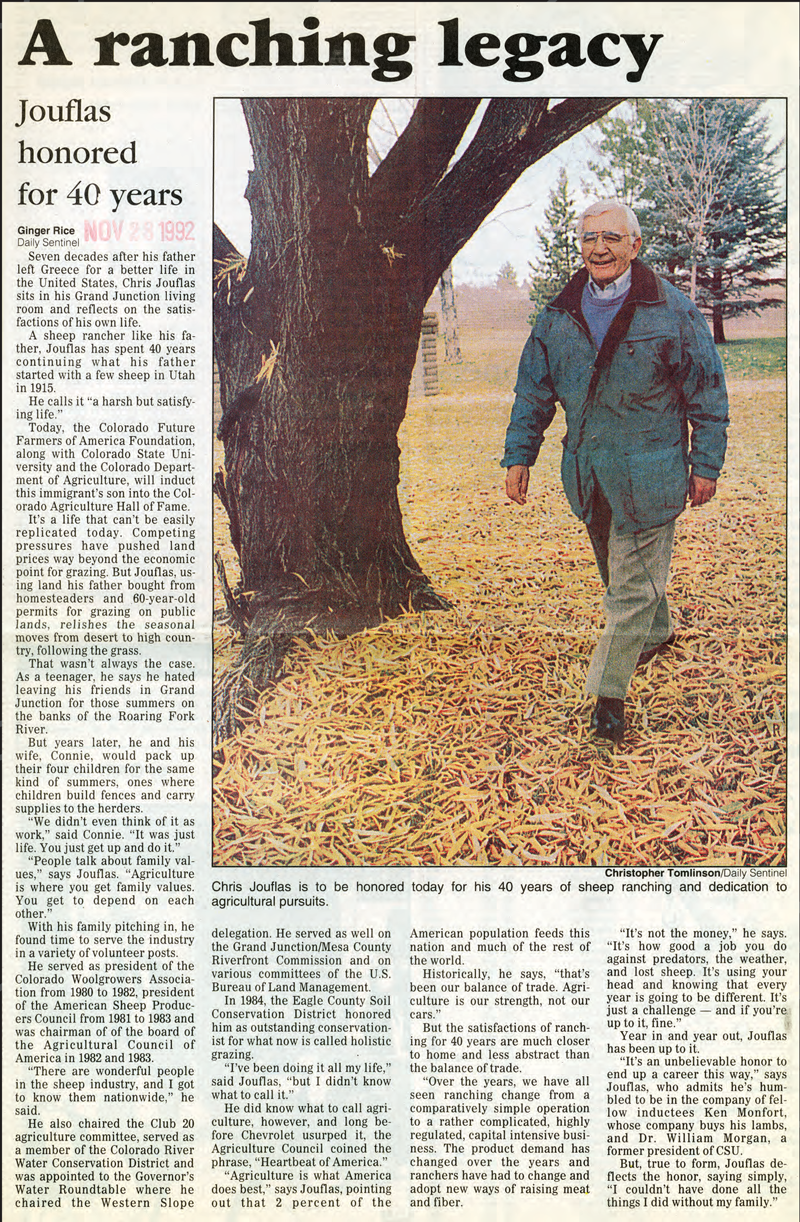

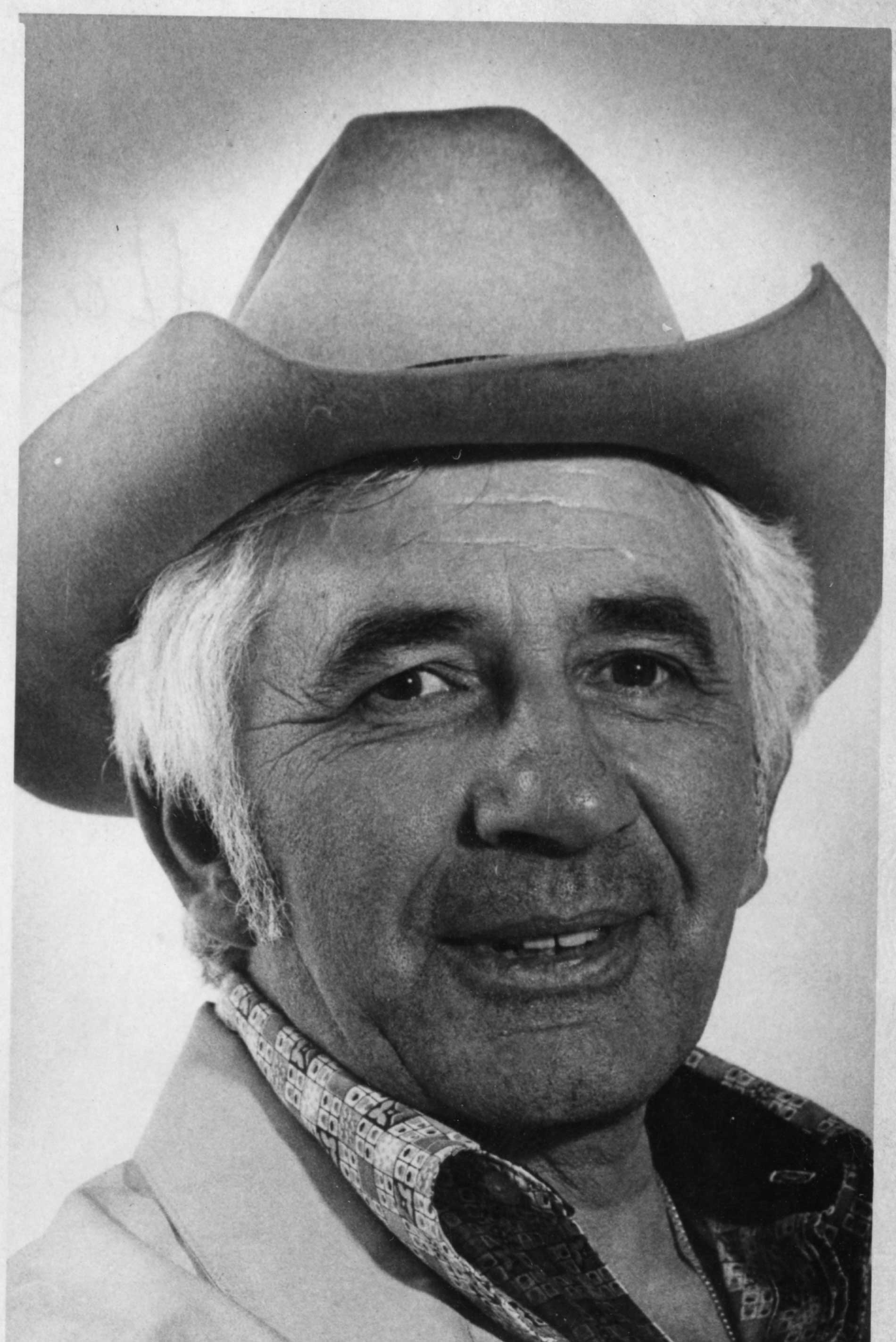

Jouflas Horse Trail and Campground

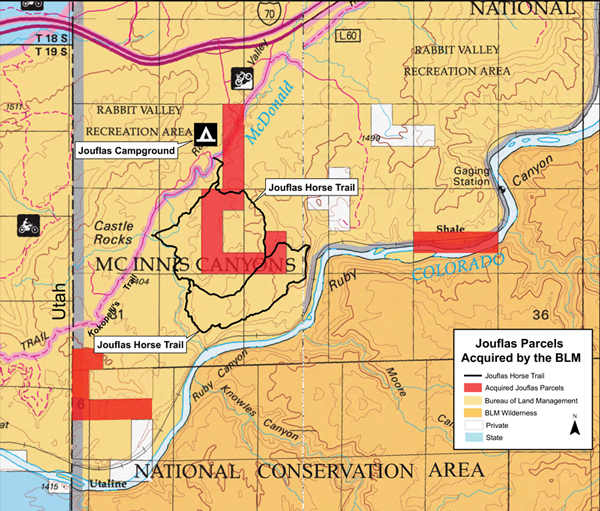

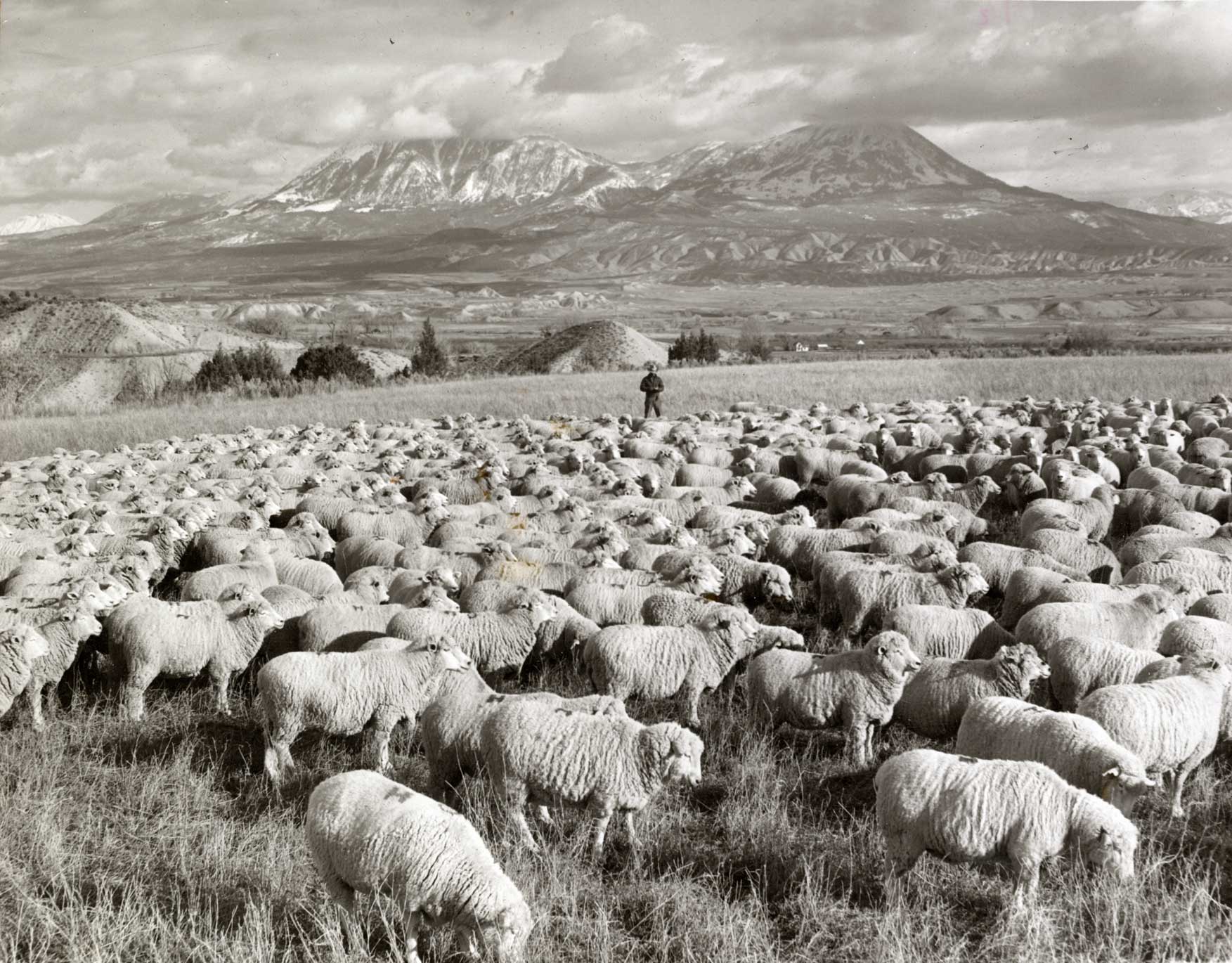

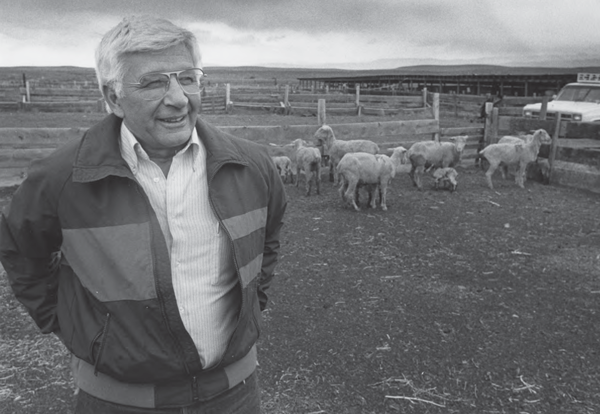

Located in Rabbit Valley, just shy of the Utah border, is the Jouflas Horse Trail and Campground in the McInnis Canyons National Conservation Area. Both are named for the Jouflas family, one of the more significant sheep ranching family in western Colorado who used public land.

Peter Jouflas migrated to the United States from Greece in 1907 and was joined in 1916 by his wife Dorothy. In 1915, Peter tended sheep in Utah and Snowmass, Colorado, and in 1918 bought a ranch on the Frying Pan River in Basalt. Sheep were kept in the high country during summer and in winter were brought to the deserts of eastern Utah and western Colorado. At one time, the Jouflas family ran roughly 20,000 head, making their ranch one of the largest sheepherding operations in North America.

Peter and Dorothy had two children – George, born in 1924, and Christopher, born in 1926. The brothers helped run the family sheep business for decades. In the 1960s, George left full-time ranching for a career in real estate. Chris, however, never left the ranching life. For half a century, he ran sheep along the Roaring Fork River and in the desert country of western Colorado and eastern Utah, in what is now part of the McInnis Canyons National Conservation Area (MCNCA). Chris recorded several oral histories for the Museums of Western Colorado. These recordings provide an outstanding opportunity to understand the many changes to the land the Jouflas family and other area ranchers encountered over the decades. These ranchers saw firsthand how increased access turned an inhospitable landscape into profitable ranching and later provided for the outstanding recreational opportunities we know today.

Not only was Chris a skilled rancher, he was also an advocate for conservation of the land. “We didn’t destroy the land,” he recalled in a 2010 interview. “We had to live off it and to destroy it would be suicide.” Chris served several terms as the President of the Colorado Woolgrowers Association and President of the American Sheep Producers Council, and was on numerous committees for Club 20, the Colorado River Water Conservation District, and the Governor’s Water Roundtable. In 1992, Chris was inducted into the Colorado Agriculture Hall of Fame. He passed away in 2013.

The Jouflas family sold over 1,300 acres of land to the Bureau of Land Management in 2006. In 2009, the BLM honored the family by naming a horse trail in the McInnis Canyons National Conservation Area after them. The Jouflas Horse Trail recognizes the long-lasting emotional connection and mutual stewardship between the Jouflas family and the lands protected by the NCA.the Bureau of Land Management.

The Old Spanish Trail: North Branch

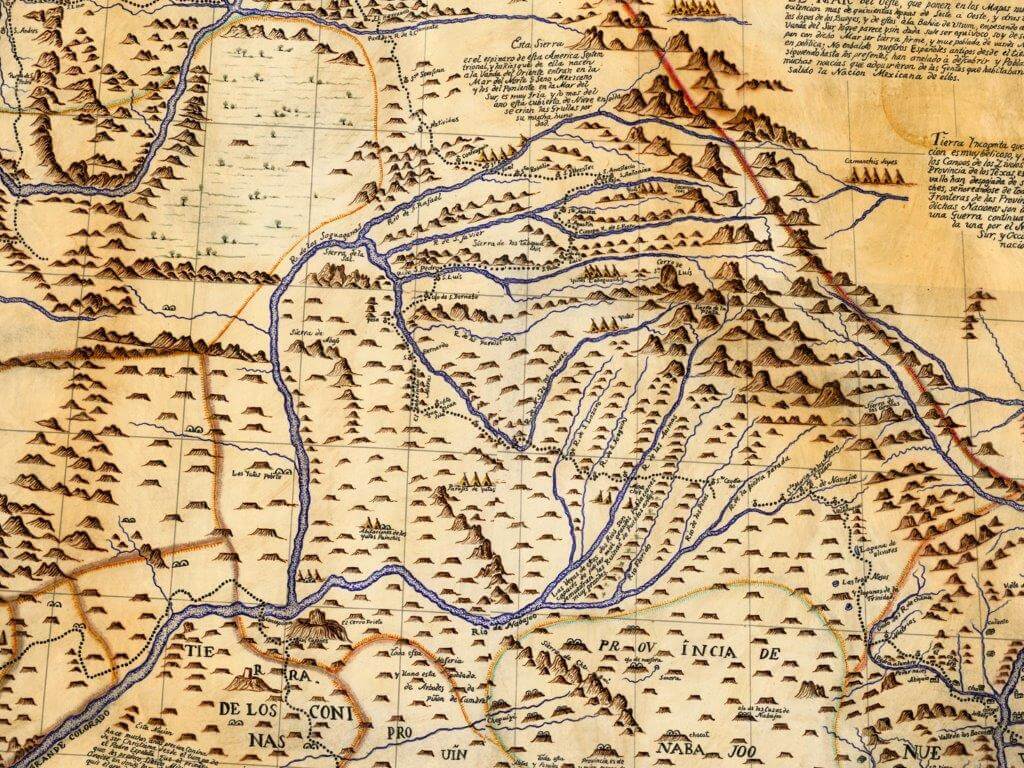

The first known European explorer in Western Colorado was Spaniard Juan Antonio María de Rivera, who in 1765 traveled from New Mexico (then a Mexican province) to what is now Delta, Colorado. Eleven years later a larger Spanish party under the direction of two Franciscan priests – Francisco Atanasio Dominguez and Silvestre Vélez de Escalante – departed Santa Fe in search of a route to Monterey, California. The priests explored over the Uncompahgre Plateau, past modern-day Montrose, Colorado, north across the Gunnison River, over the Grand Mesa and Roan Plateau, and into Douglas Canyon before traveling into what is now Utah. Dominguez and Escalante did not reach California; they did, however, produce the first detailed maps and written accounts of the lands and indigenous people to the north and west of New Mexico, piquing interest in the area and the possibility of opening a trade route between Santa Fe and the Pacific Ocean.

It would take another 53 years to complete the overland route to California. In 1829 Santa Fe merchant Antonio Armijo successfully led 60 men and 100 mules to Los Angeles along a route that became known as the Old Spanish Trail. Variations soon followed, among them the Northern Branch, which left from Santa Fe toward what is now Saguache and Gunnison, Colorado. The trail eventually crossed the Grand River (now called the Colorado) just outside of present-day Grand Junction and passed through the McInnis Canyons National Conservation Area before joining back with the main route near Green River, Utah.

The golden age of the Old Spanish Trail spanned the 1830s to the 1850s, as the trade route delivered textiles, livestock, and other goods between Santa Fe and Los Angeles. The interior lands along the 2,700-mile route were home to fur traders, Native Americans, and ranching communities, all of whom added to the trade. By the 1860s the trail was modified and broken into different segments, and the route in western Colorado became known as the Salt Lake Wagon Road. Early survey crews into Colorado made note of the old road as seen on this land survey map from 1881 (note that the region had just been open to settlement and the town of Grand Junction is listed as Ute).

Some of the only recognizable evidence of the Old Spanish Trail in Colorado is found on Public Land between Grand Junction and Delta. The trail in this section parallels the modern U.S. Highway 50. One of the locations is a four-mile hiking trail through the Gunnison Bluffs just south of Grand Junction. The second is marked by a roadside historic marker on the northeast side of Highway 50 approximately 15 miles west of Delta.

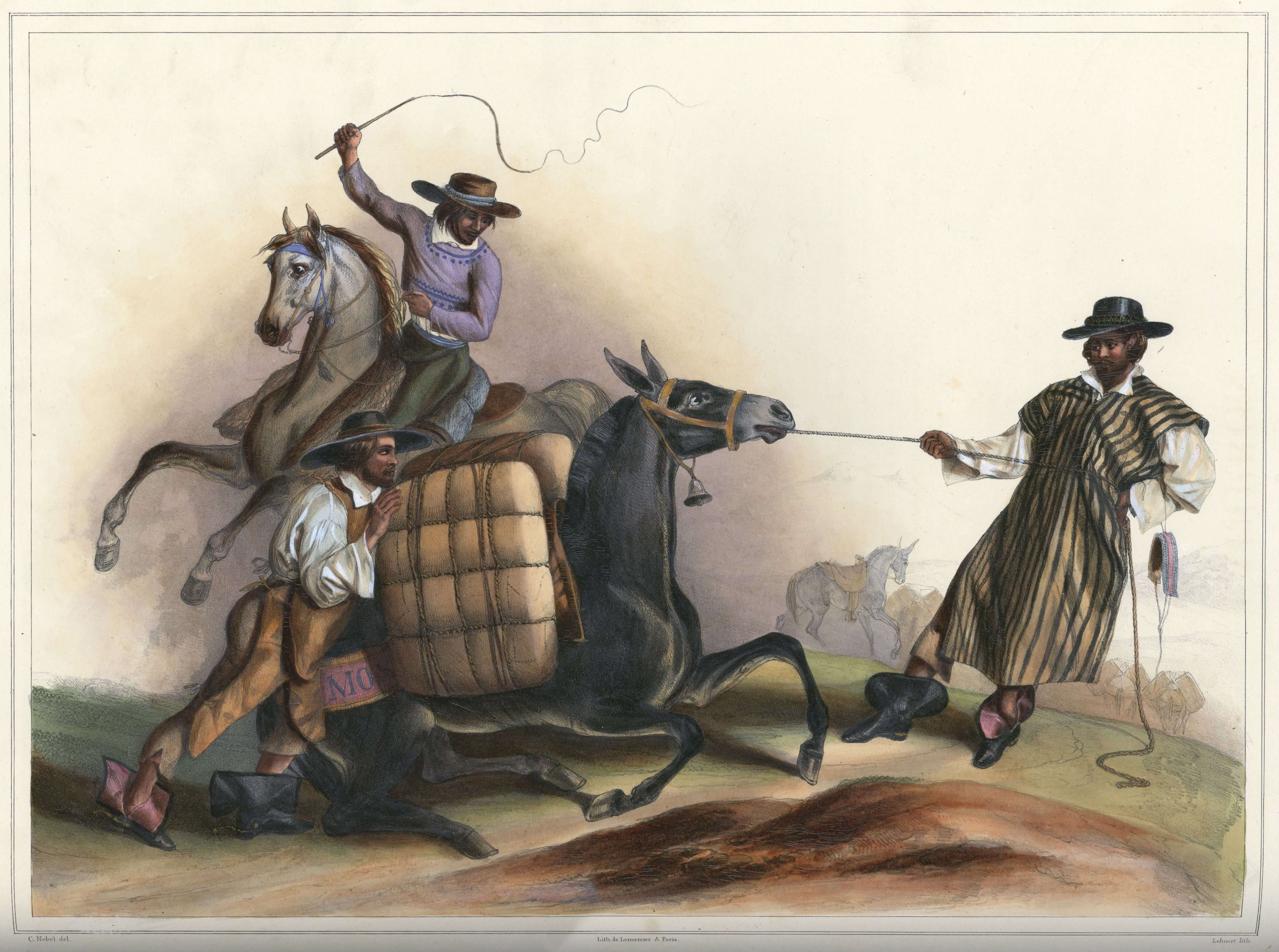

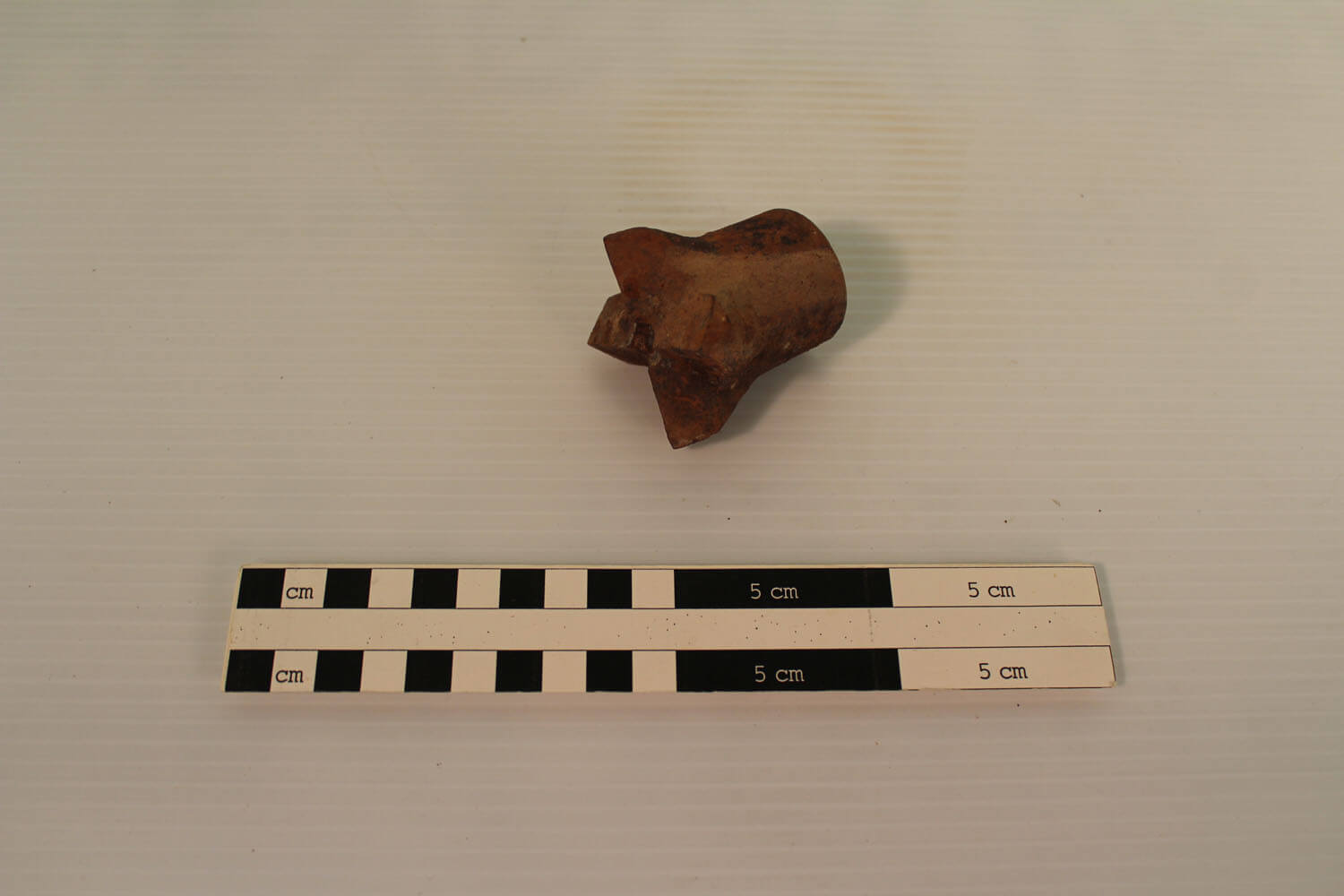

Spanish Colonial Ring Bit Circa 1800s

Bits, stirrups, and spurs were the three principal articles of iron considered necessary by the Spanish horsemen. This Spanish iron bit, was known as known as a desvenado, was used to apply pressure on the horse’s tongue and mouth to give the rider control. The iron ring was used to encircle the horse’s jaw and keep it in place. The Spanish bit is much smaller then a modern bit because the Spanish horse breeds and mules were much smaller in stature. The bridge of the bit has four holes that were originally used to attach jingles, known in Spanish as coscojos, which were decorative art and made a pleasant sound when traveling. A Spanish Colonial blacksmith added the decorative motifs on this bit by filing, stamping, and piercing the iron. The jingle bits were popular with both Spanish and Ute horsemen.

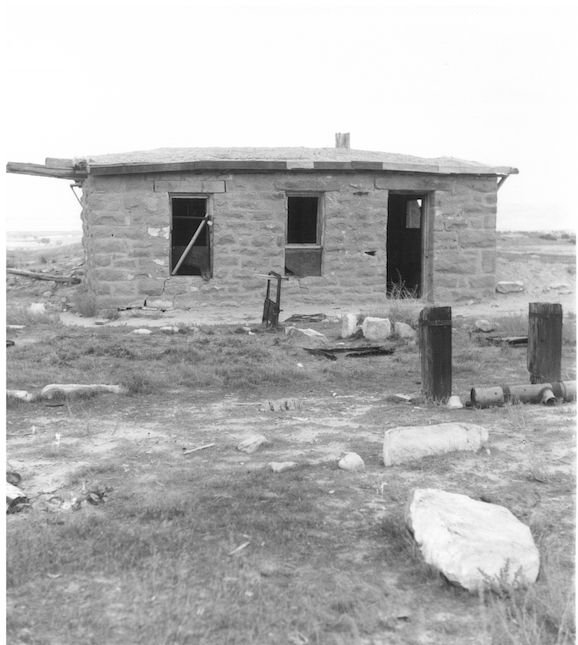

Skinner Cabin – A Homestead Site

Sometime between 1905 and 1910, a stone cabin was built in the Fruita Paleontological Area just outside of the town of Fruita. It is believed that John Skinner, a stonemason, built the cabin. We don’t know why Skinner built his cabin in such an isolated location, with no trees or good water immediately available. We also don’t know how long he lived there. The last person known to have lived in the cabin was John Condon, an injured World War I veteran who lived there in the 1940s and early 1950s. Condon had no car or horses, but he would walk to Fruita for supplies. Condon started digging up and selling dinosaur fossils he found near his cabin.

In 2016, the BLM partnered with HistoriCorps, the Museums of Western Colorado, and Colorado Canyons Association to restore and protect the Skinner Cabin. HistoriCorps provided volunteers, including skilled masons and woodworkers, who worked on the cabin for three weeks, replacing missing stones and rebuilding the roof. This is an important historic resource for everyone to visit and admire. Visitors to the cabin can peer inside to see where previous inhabitants may have stored water on the east wall, and where there may have been shelves on the north wall.

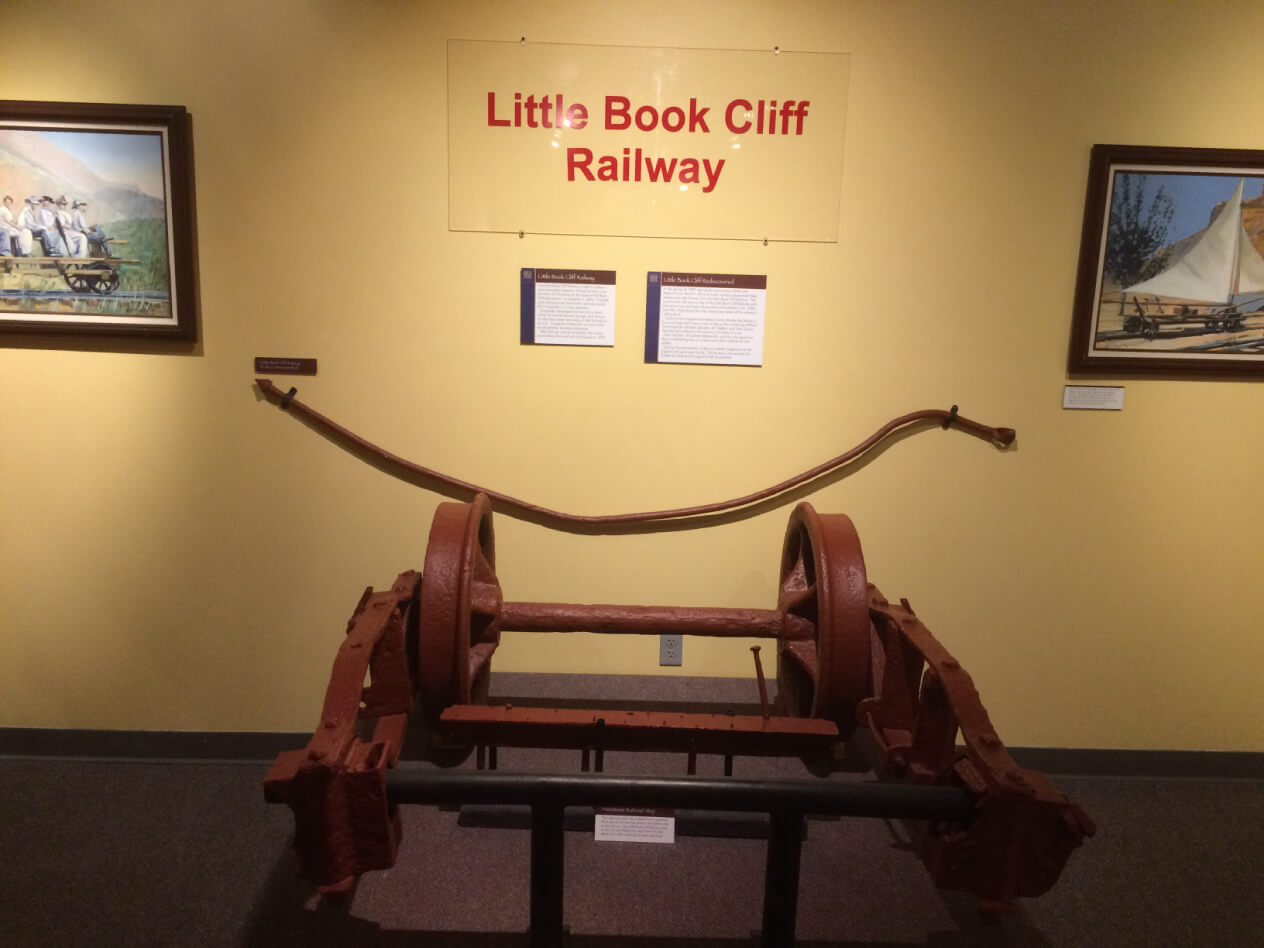

Little Book Cliff

On Sept 11, 1889 William Carpenter and several other business men of Grand junction, CO founded the Little Book Cliff Railway. The LBC was built narrow gauge, the rails were only three feet apart. The reason for the building of LBC was to haul coal from the Book Cliff mine and supplies from the standard gauge D&RG or CM railroads to the mining town of Carpenter 12 miles distant from GJ.

The line climbed from the valley floor in downtown GJ to the foot hills of the Book Cliffs. The most interesting feature along the line was its double-horseshoe curve about 8 miles outside of Grand Junction just north of what is now the regional airport. It was there that most of the road’s accidents occurred. The worst was when Locomotive No. 4 the RRs largest rolled on its side.

Since the only commodity of on the LBC was the coal the RR tried to generate extra revenue thru excursions. At one time the idea of renaming the town of Carpenter to Poland Springs was floated to entice more rides. The LBC also constructed large riding cars for tourist from GJ. The riders, called Go Devils, were towed to Carpenter on the back of a train. The adventurous could then climb aboard and go ‘like the devil’ on the return to GJ. Sails were added as an experiment for more speed and a way for the riders to be powered uphill, but they did not work out.

In 1923 the Bookcliff mine closed, thus the Little Book Cliff Railway closed and was scrapped. Very little of the LBC was saved. However, a damaged fright car truck was left behind and was unintentionally buried in the LBC’s rail yard in downtown Grand Junction. The truck was discovered during the construction of the Mesa County Court house in 2000 and is now on display at the Museum of the West.

The Rio Grande Chapter of the National Railroad Historical Society has made a replica of one of the LBC’s Go devils as well as a handcart. These replicas can be found at the Cross Orchards Historic Site in Grand Junction, CO.

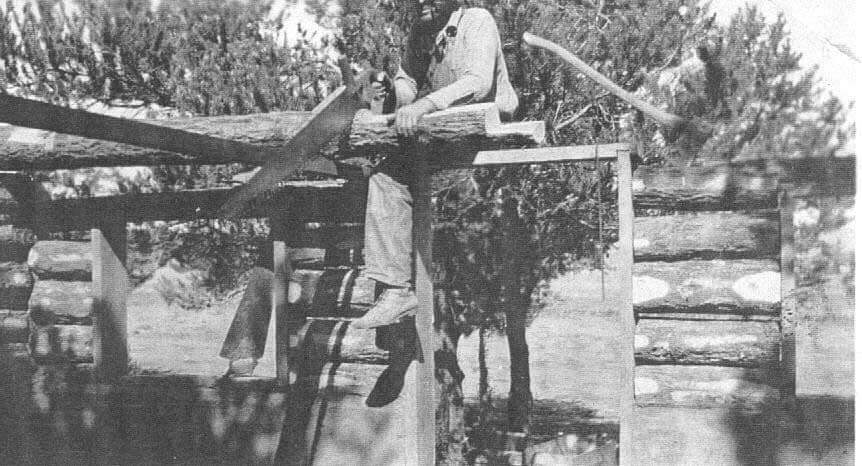

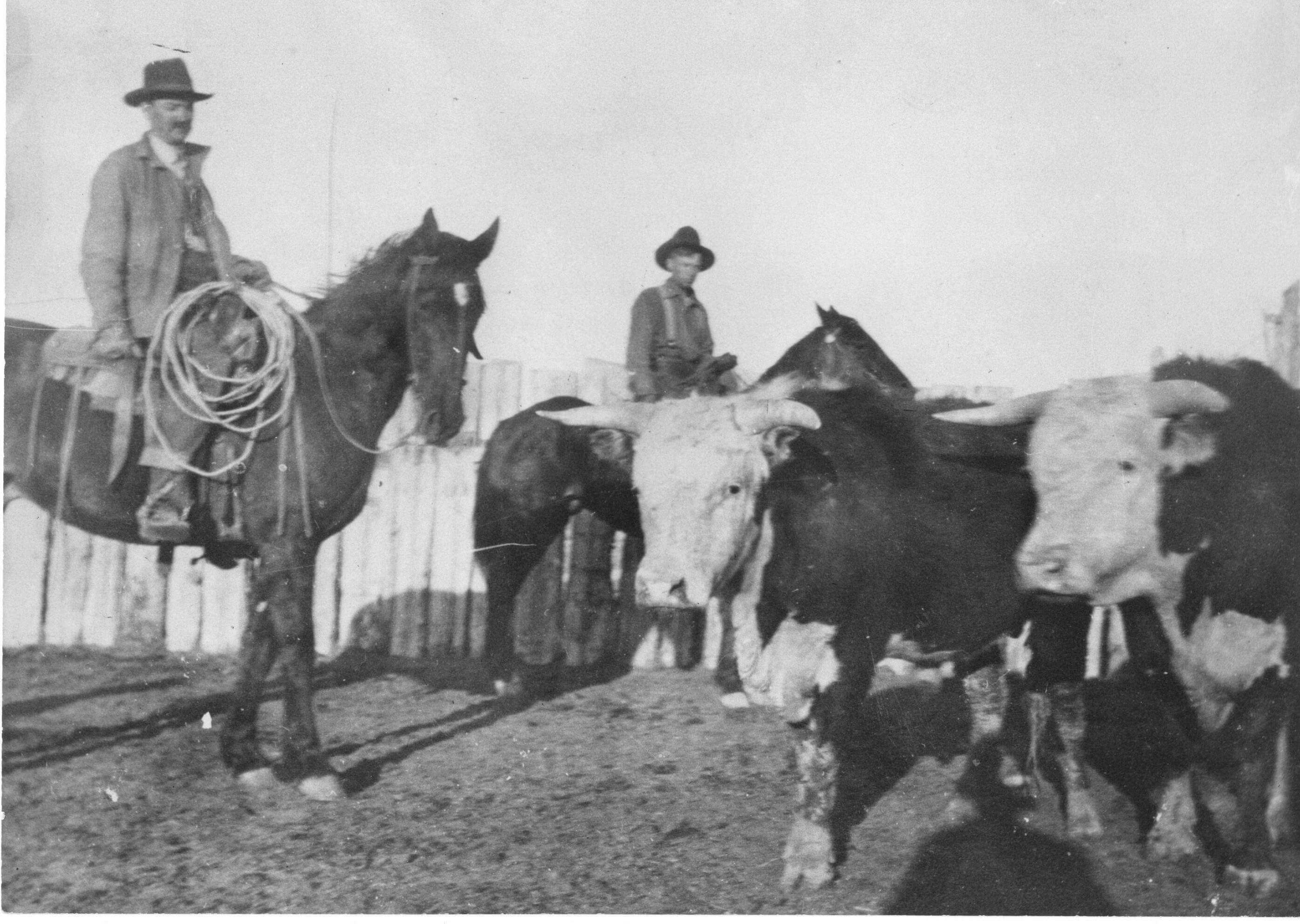

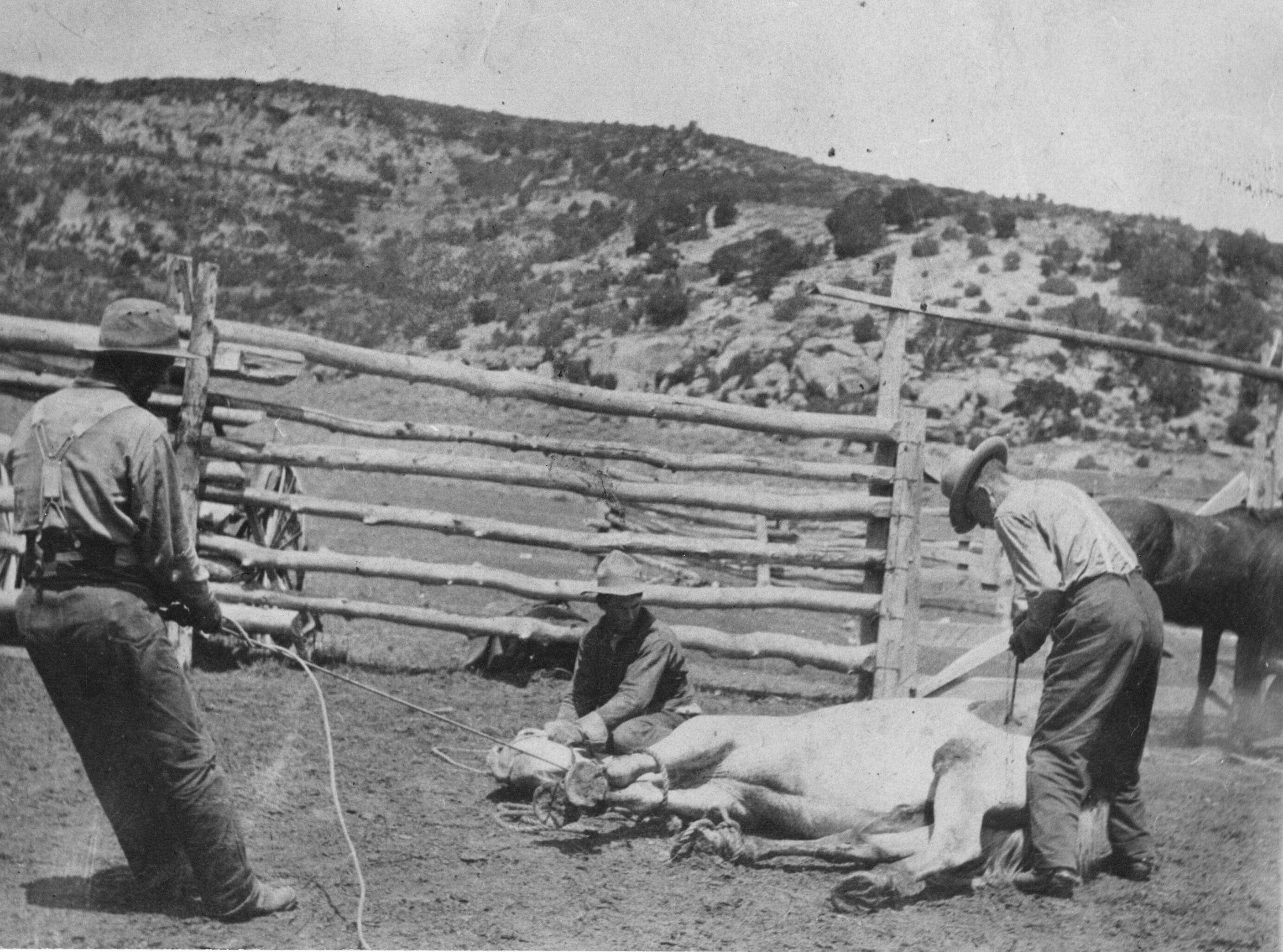

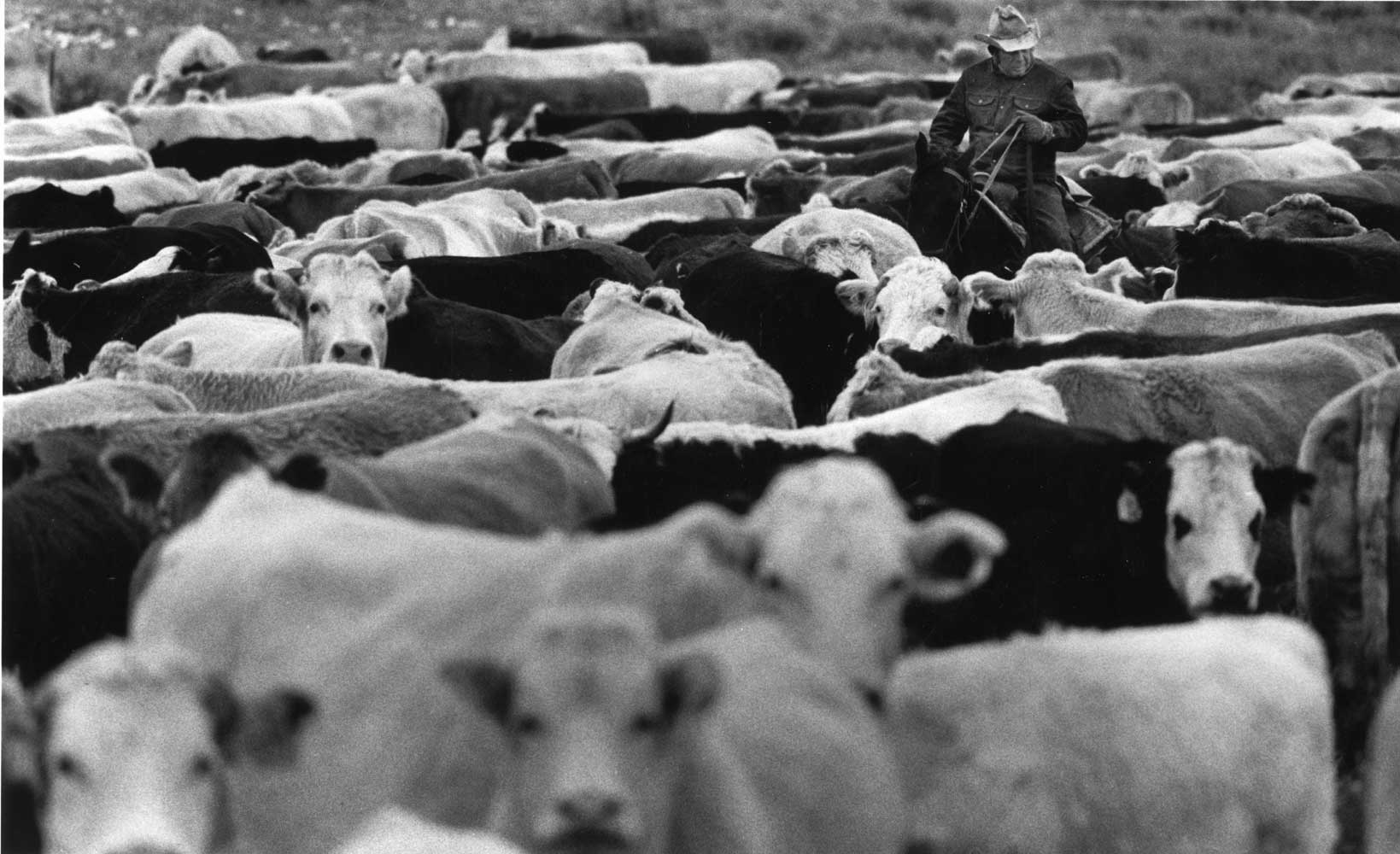

Ranching

Ranching in western Colorado covered a short but important period between the late 1850’s and the late 1880’s. As the Colorado territory opened up, cowboys moved in, coming from Texas with herds of cattle. The open range was vital to ranchers, who viewed it as perfect land for livestock to roam freely. Ranchers relied on public lands to provide feed for their herds. It was common to have multiple companies working the same land at the same time. Brands were used to tell which cattle belonged to which company. Brands became an important symbol of the American West. As ranchers began to settle in Colorado, they laid claim to huge pieces of land, which housed thousands of cattle, making the owners very wealthy. They became known as “Cattle Barons.” Fighting over public lands became more and more common because large companies needed more and more land to feed their herds.

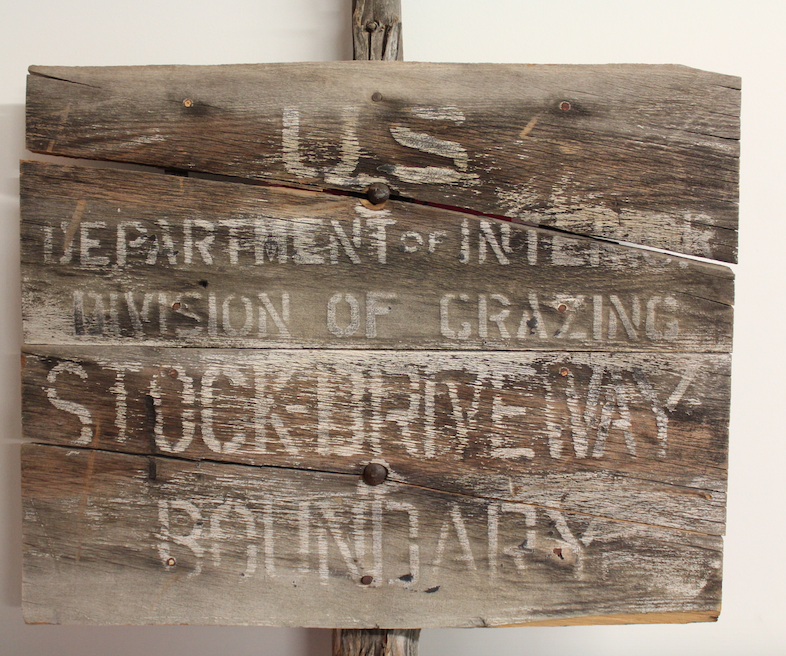

Not only were cattle companies fighting over pasture, but they were also fighting against the competing sheep market. Known as the Range Wars, sheep herders and cowboys alike fought for grazing land, often with deadly consequences. Anglo-American cattlemen disliked the notion of sheepherding. The highly romanticized life of the cowboy did not extend to herders. Many woolgrowers, therefor, hired Mexican-Americans or Mexican nationals to tend their flocks. The racial prejudices made the tensions between cattlemen and sheep herders worse. In 1884, the Western Stockgrower’s Association was formed by cattlemen around Grand Junction with the purpose of stopping sheep herders from accessing the area. In 1886, between Whitewater and Delta, a flock of sheep and its herder were killed by cowboys. In 1894, 50 hired gunslingers rimrocked (drove over a cliff) 4,000 head of sheep. In 1915, Mrs. Nancy Irwing’s herd of Angora goats were driven over a cliff, a Mexican herder was killed and Mrs. Irwing’s cabin was set on fire. Violence continued well into the 20th century. In the 1930’s, Fruita folk-hero Charlie Glass, an African-American cowboy, was killed by sheep herders in retaliation for Glass’s shooting of sheep herder Felix Jesui ten years earlier. In 1934, the Taylor Grazing Act was passed, changing grazing rights on public lands. The bill set up the Grazing Bureau who ran the range lands. The grazing service and the General Land Office merged in 1946 to form the Bureau of Land Management.

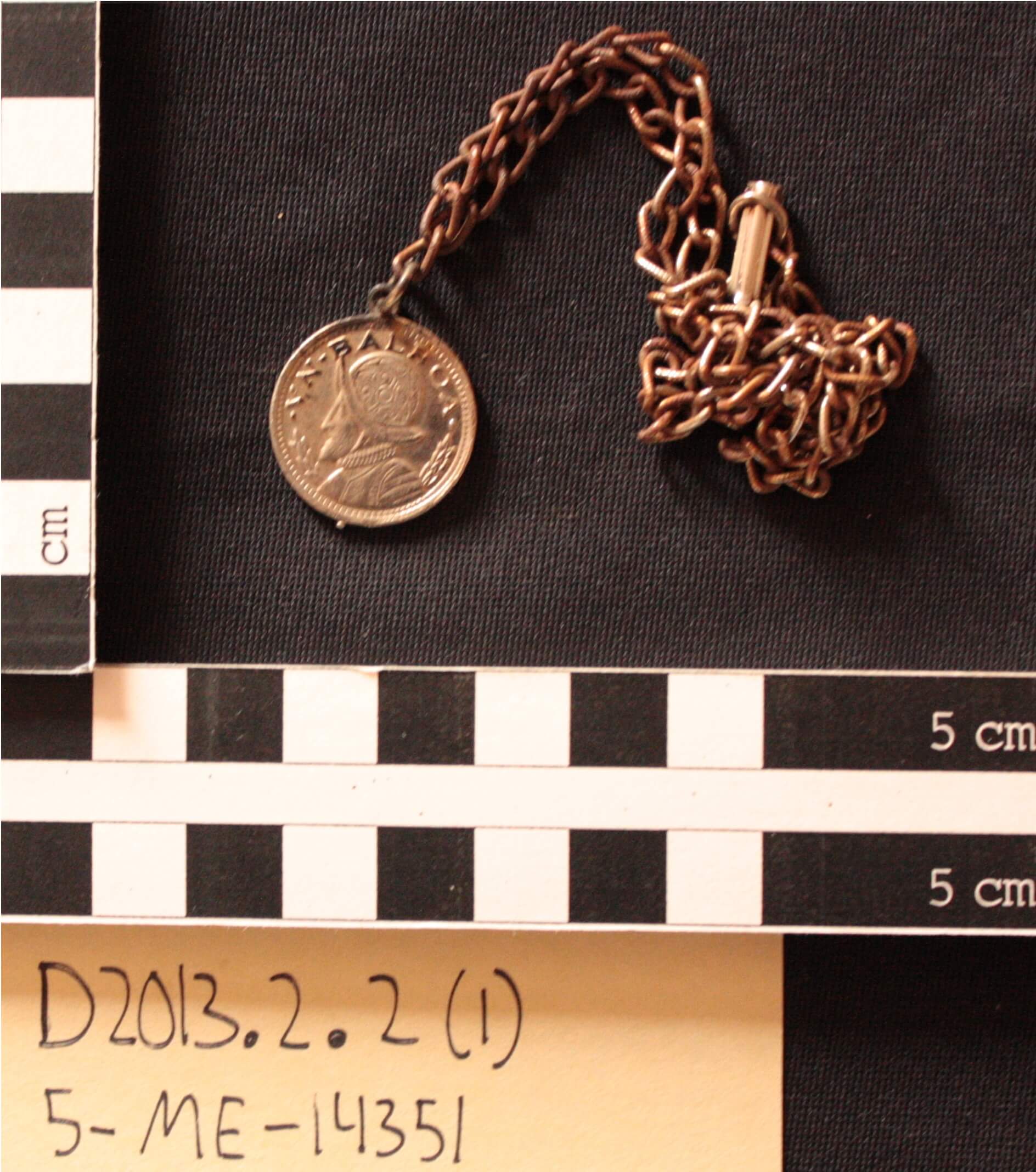

Faux V. N. Balboa Coin Medallion and chain Circa 1931

This faux coin medallion has a profile portrait of Spanish explorer Vasco Núñez de Balboa on the front and an early Spanish galleon on the reverse side. The Balboa medallion was patterned after an actual Panamanian coin. Attached to the medallion is a heavy chain and clasp. The medallion may have been created to commemorate the 1930 airmail route to the Panama Canal Zone by Charles Lindbergh. Muriel Marshall’s book, Red Hole in Time, which tells the history of Escalante Canyon, mentions the area was heavily used for grazing by sheepherders from Utah and Colorado. The medallion may have been worn by sheepherder as a keepsake or adornment.

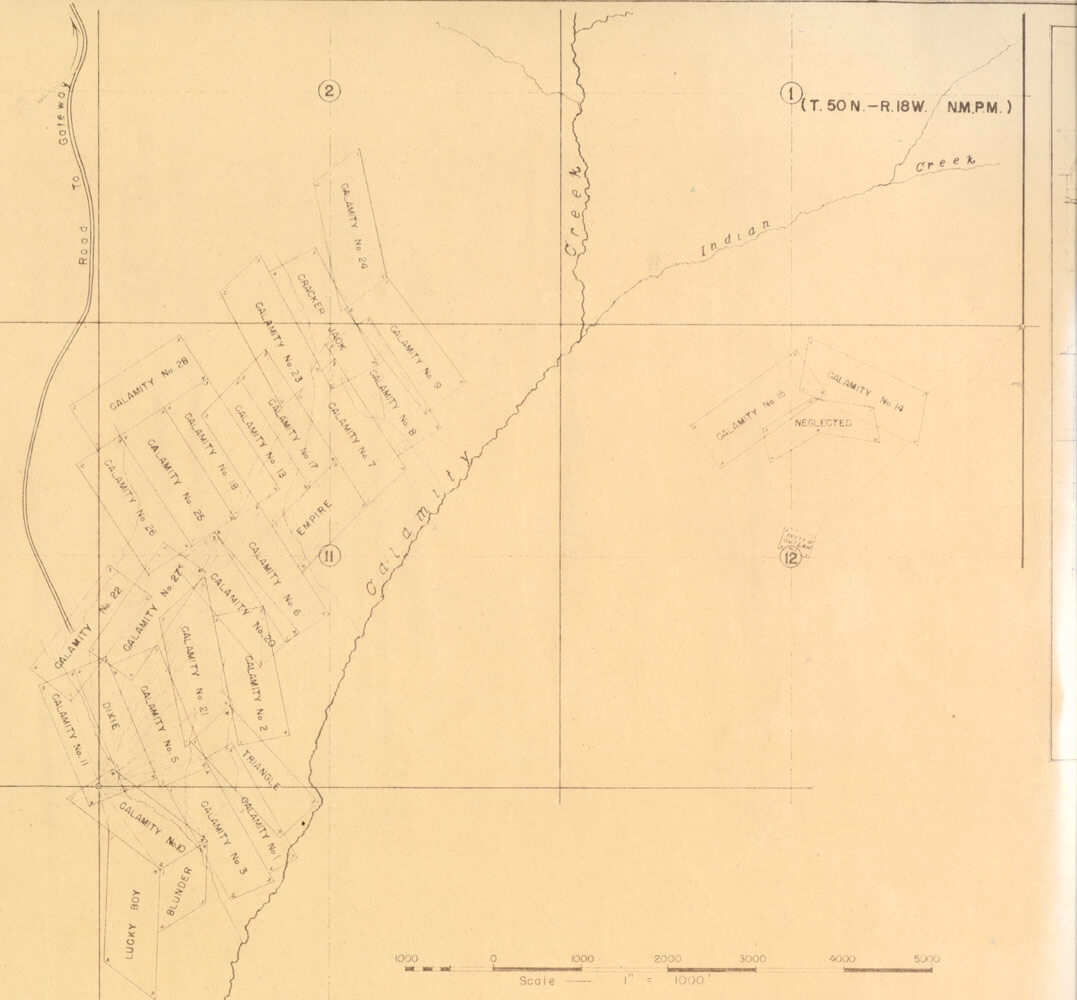

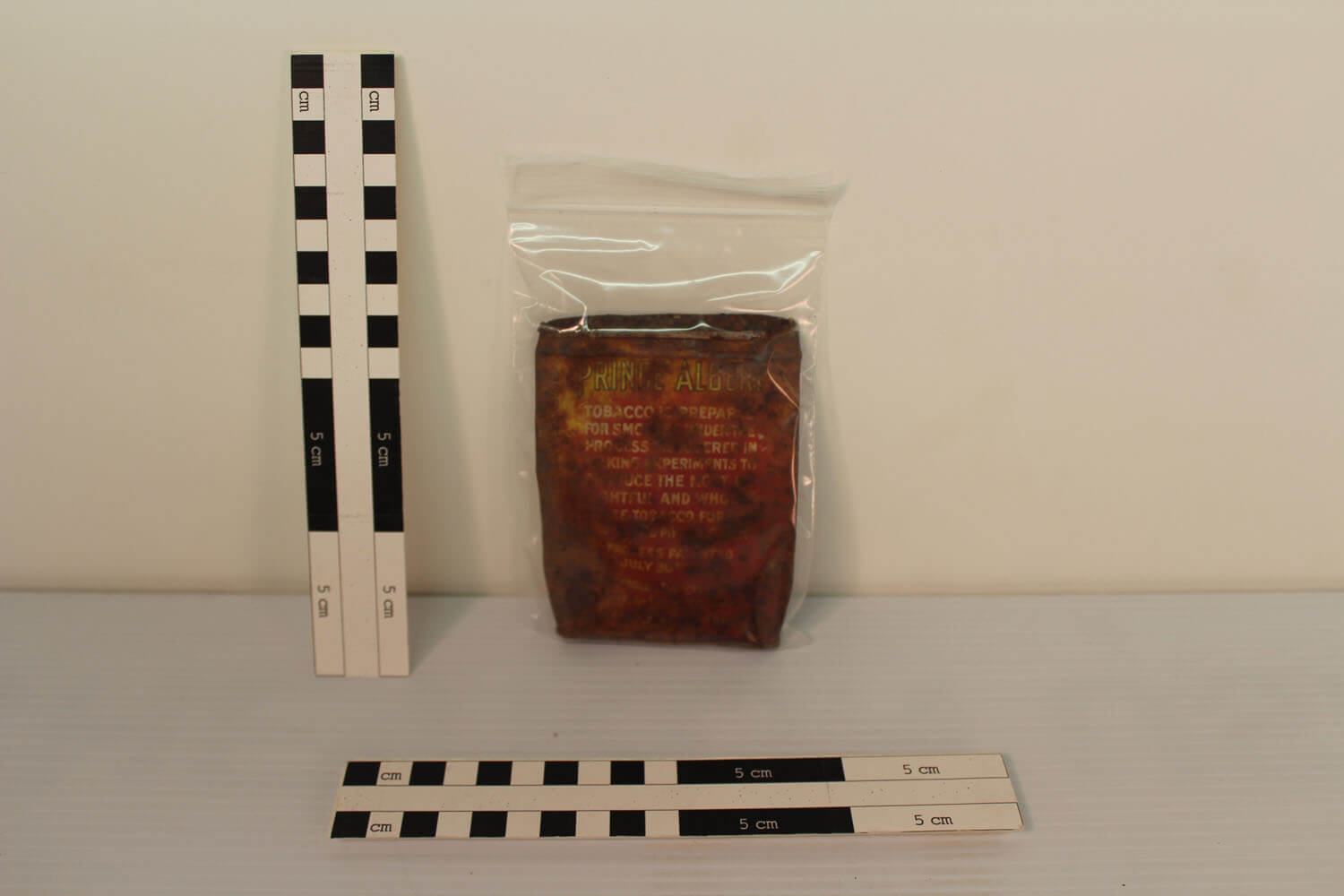

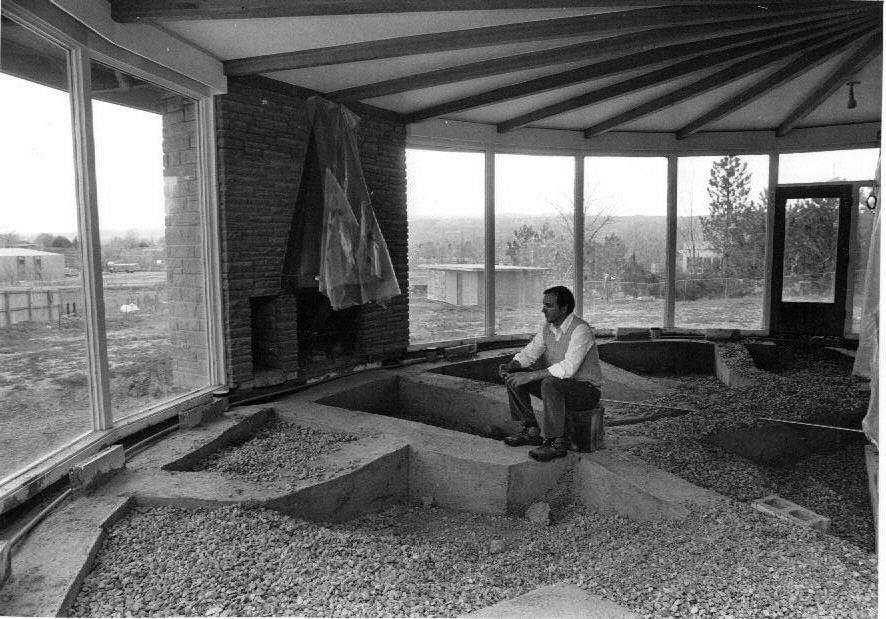

Uranium Mining – Calamity Camp

Calamity Camp, located outside of Gateway, is one of the last standing carnotite (radium, vanadium and uranium) camps in Colorado. Surviving a series of booms and busts,it was an active mining camp from 1913 to the mid 1960s. Calamity Camp was more than just a collection of mines. It was a community for hundreds during the twentieth century. During the uranium boom, Calamity Camp was just short of being a small town. Miners from all over the region would gather at Calamity. From 1957-1959 a school taught by Gertrude Day was opened at Calamity. A voting precinct was even established at Calamity Camp for the 1956 elections.

Each generation that lived at Calamity experienced a different way of living. The first radium miners lived a rugged and difficult life filled with uncertainty. The last group of uranium miners still lived a harsh lifestyle but luxuries like electricity, running water, and regular access to Gateway and Grand Junction were common. Oral histories collected from those that lived at Calamity Camp give us an understanding of what everyday life was like. Check out some of their stories here or at the Museum of the West.https://mesacountylibraries.org/mcohp/

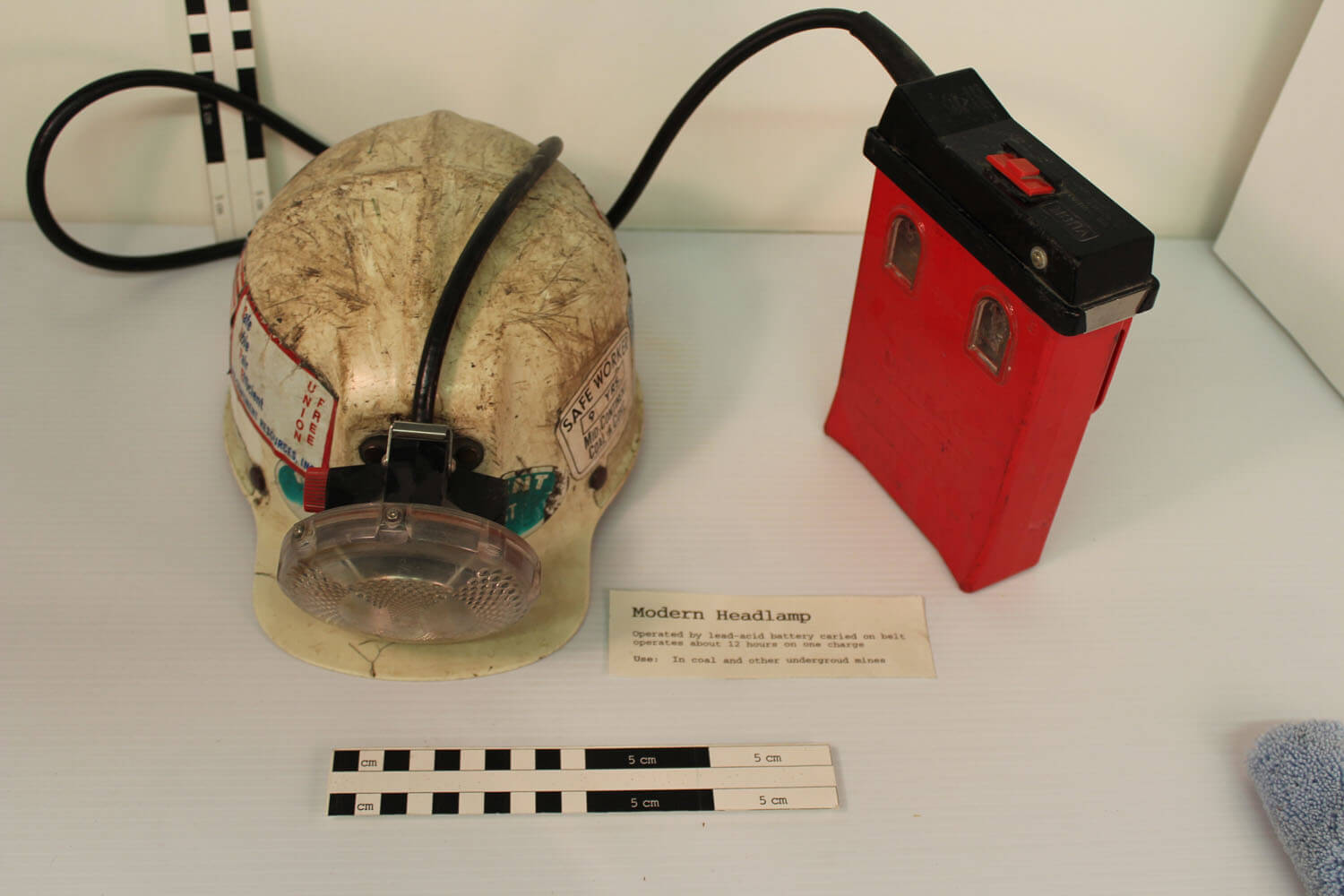

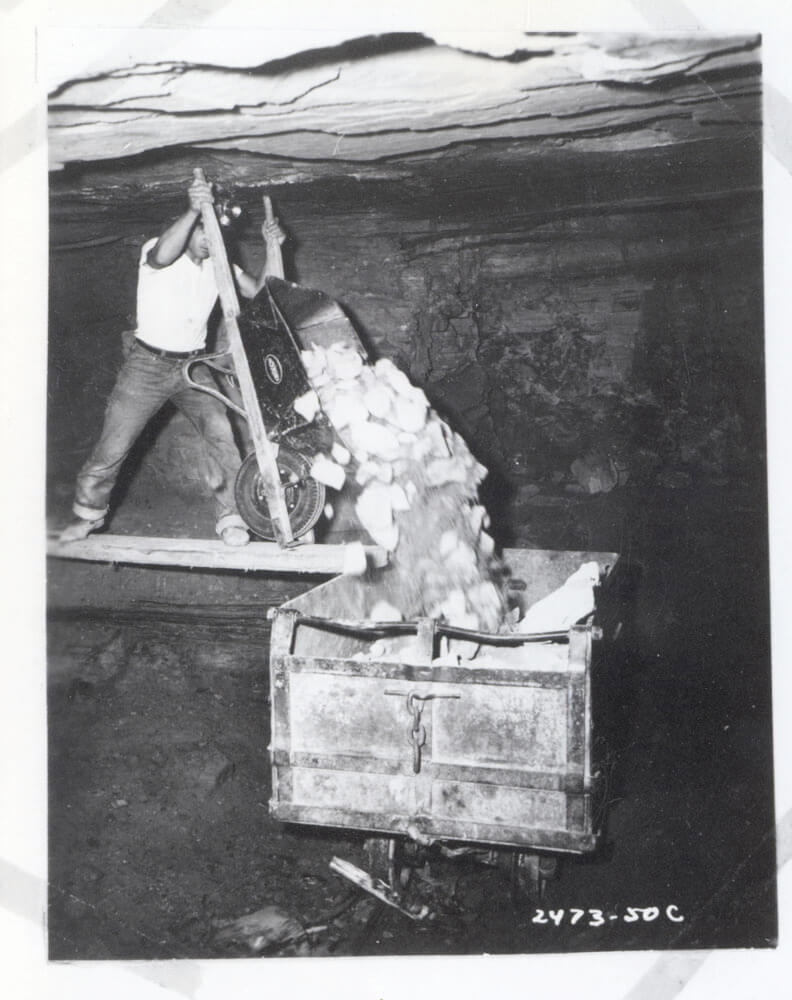

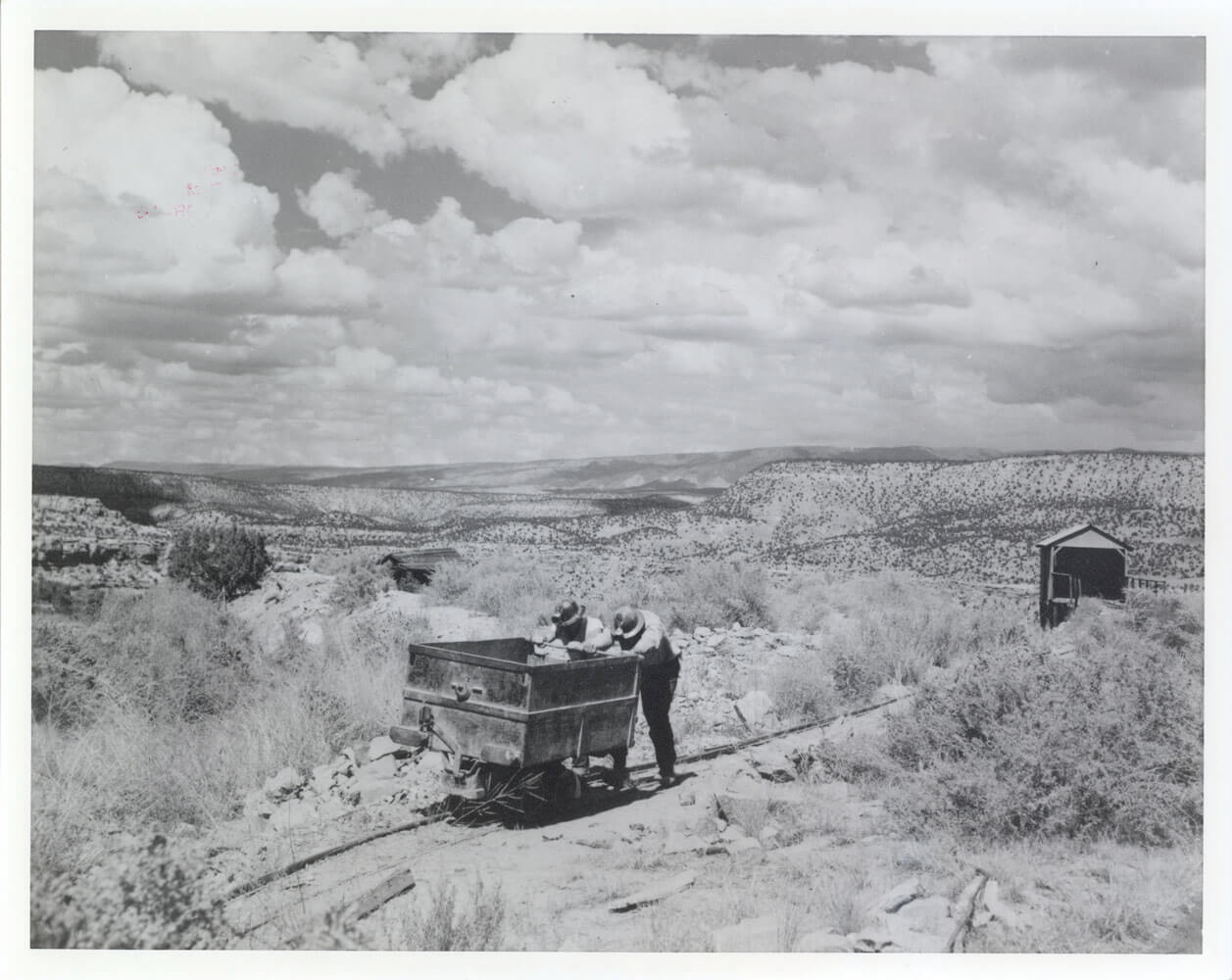

Mining on Calamity Mesa was basic hard rock mining. Drill bits would be pounded into the hard rock of the Morrison Formation to create a series of deep holes. In the early days, these drills were hammered in by hand. Later, air compressors were used to power machinery. After a series of holes were formed, they were filled with dynamite and ignited. The explosion would blast out rock, which was then collected and hauled away. There were very little health and safety regulations in the mines in the early days. Lack of ventilation in mine shafts, the use of explosives and machinery, and exposure to radioactive materials were constant dangers.

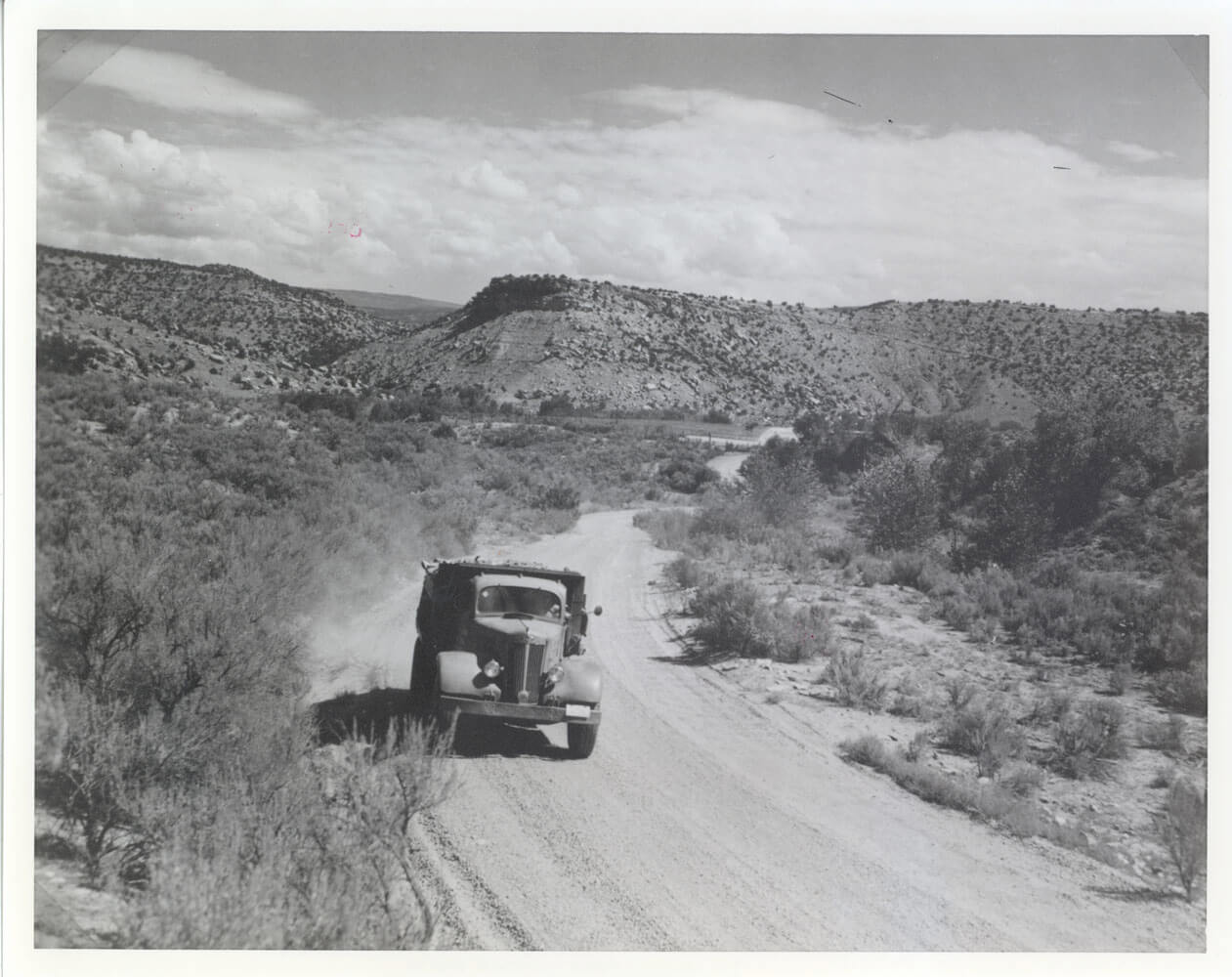

In the 1920’s,a road from Gateway to Calamity was cut into the plateau allowing greater access to the remote Calamity mines. After the radium boom, a vanadium mill was opened in Gateway that processed carnotite from Calamity. During the early 1940s, efforts shifted to processing uranium and mills were opened all over the Colorado Plateau including in Grand Junction, Naturita, and Uravan. Once the ore was mined, the uranium had to be extracted from the rock. The ore typically only had a small percentage of uranium in it. It went through a milling process where the rock was pulverized then mixed with water, creating a slurry. The slurry was mixed with sulfuric acid that stripped the uranium from the rock. Once removed from the slurry, the uranium oxide or yellowcake was collected. The remaining rock slurry was pumped into a tailings dam where the tailings released their heavy metal content to the environment.

Before the devastating effect of Uranium were widely understood, mill tailings were simply spread along rivers or dumped out in piles around the mill. In many cases, the tailings were sold and used as backfill in construction projects in nearby towns. From 1950 to 1966, radioactive tailings were sold to more than 4,000 private and commercial properties in the Grand Junction area alone. In 1966, the Colorado Department of Health started to have concerns about the potential health effects the mill tailings were having on area residents. They sampled tailings for radon-222, and found the tailings to be emitting harmful radiation levels. The 1978 Uranium Mill Tailings Remediation Actbrought to light the hazards of uranium mining waste and a large-scale cleanup began.Mill tailing cleanup projects are still in effect and disposal sites are carefully monitored and regulated.

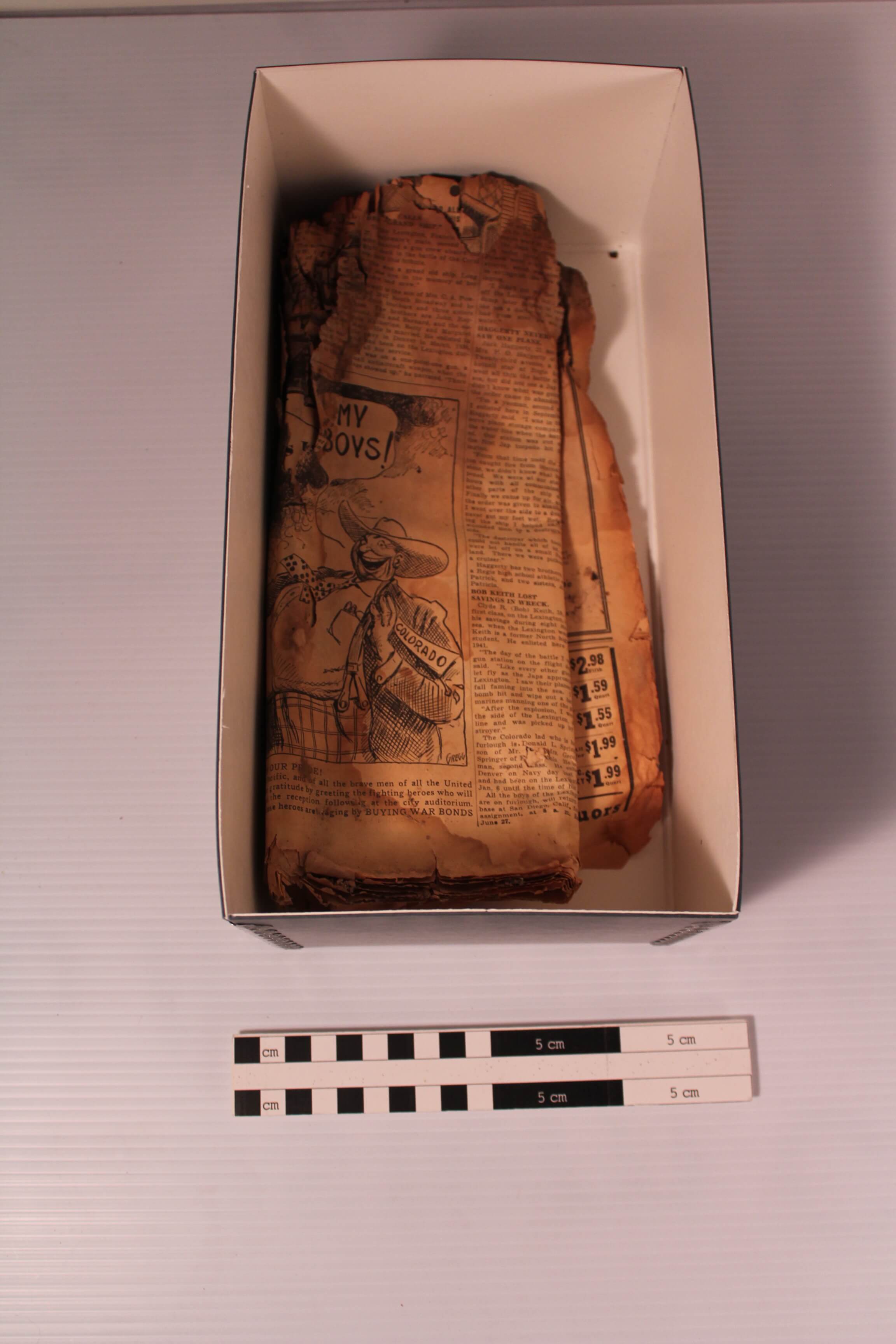

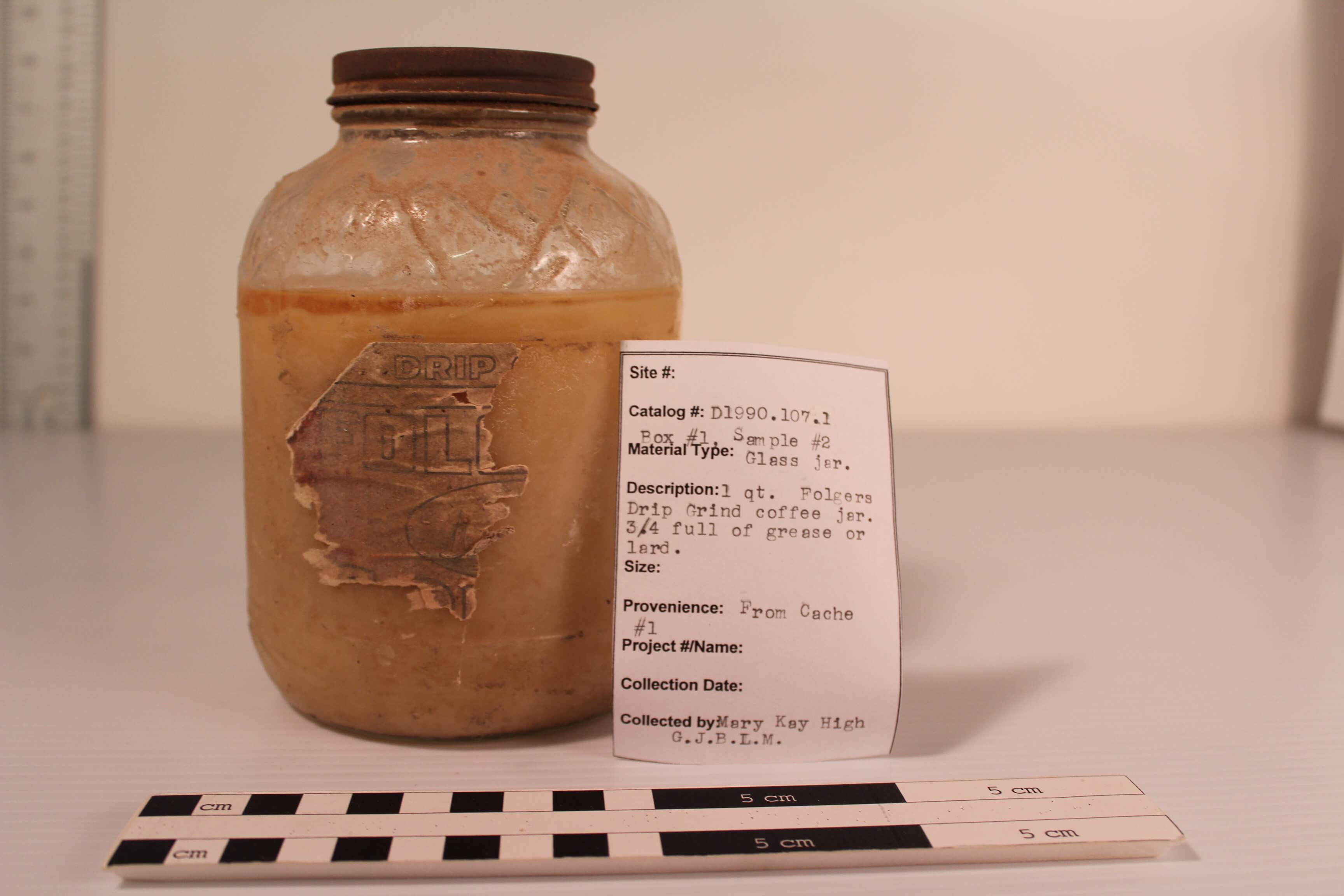

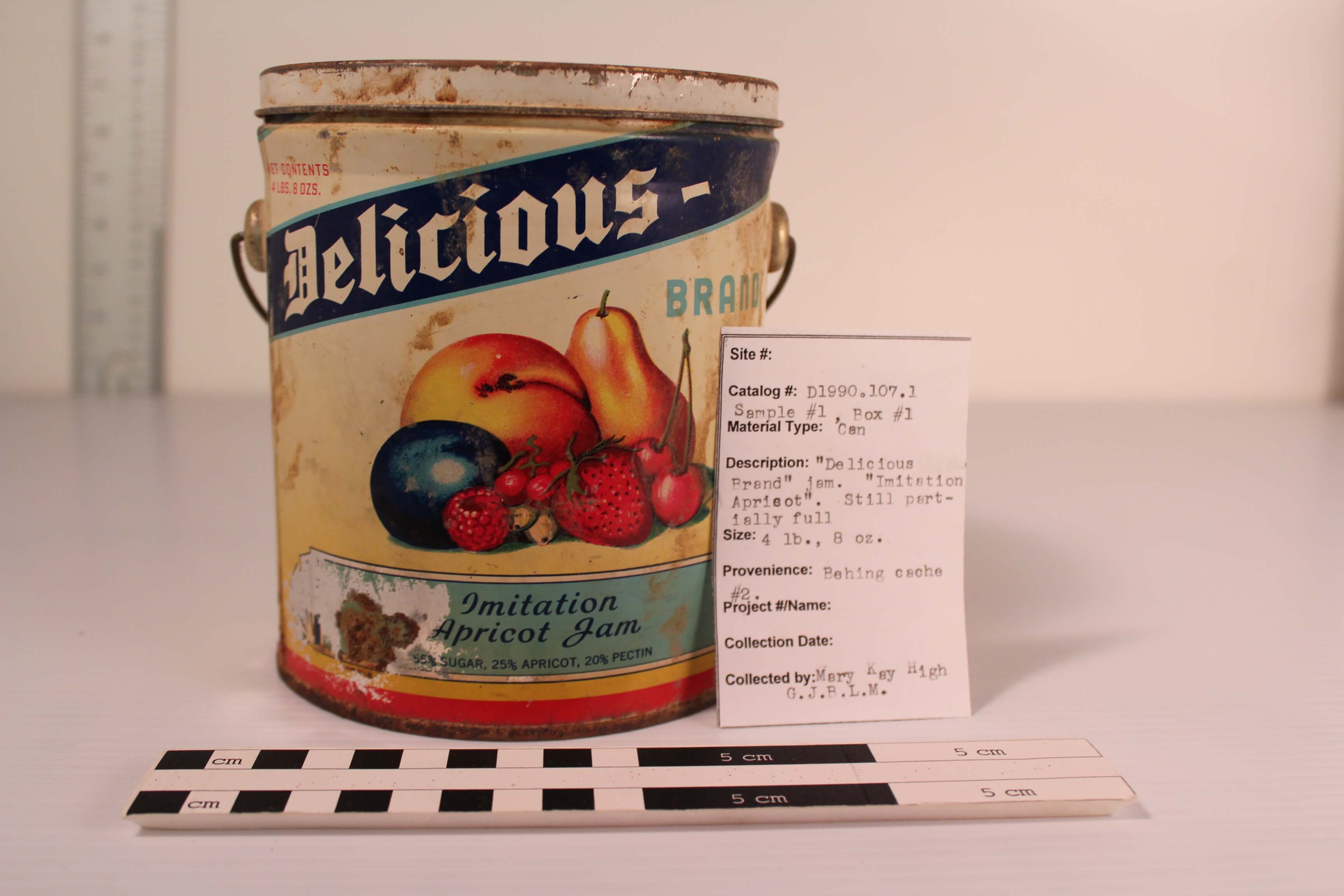

Calamity Camp and the surrounding areas began to dwindle in population after the demand for uranium plummeted in 1964. The communities on the Uncompahgre Plateau were essentially abandoned as familiesleft the area looking for new opportunities. While the people that once lived at Calamity Camp have moved on, their stories and evidence of how they lived still remain. In the early 1990s the Museum of Western Colorado started collecting oral histories from the families that lived and worked in the area. These stories provide valuable insights into what everyday life was like. In addition, historic documents such as mine claims and leases, geologic survey maps, and government reports all help us piece together exact dates and names. Some of the best information about Calamity, however, is still waiting to be discovered on the site.

Sadly, time is taking its toll on Calamity Camp. Wood cabins that have been abandoned for almost a century have collapsed. The heavy walls of the stone cabins are being threatened by water damage at their foundations.Few of the original roofs are intact which speeds up the deterioration. In 2007, the Grand Junction Field Office of the Bureau of Land Management, the Museum of Western Colorado, and Gateway Canyons Resort started a large stabilization project. New roofs have been placed on some of the stone cabins to help save the stone walls. In 2011 the property was given the honor of being added to the National Register of Historic Places Register. The National Register of Historic Places is the official list of the Nation’s historic places worthy of preservation and demonstrates the importance of Calamity Camp on a national level.

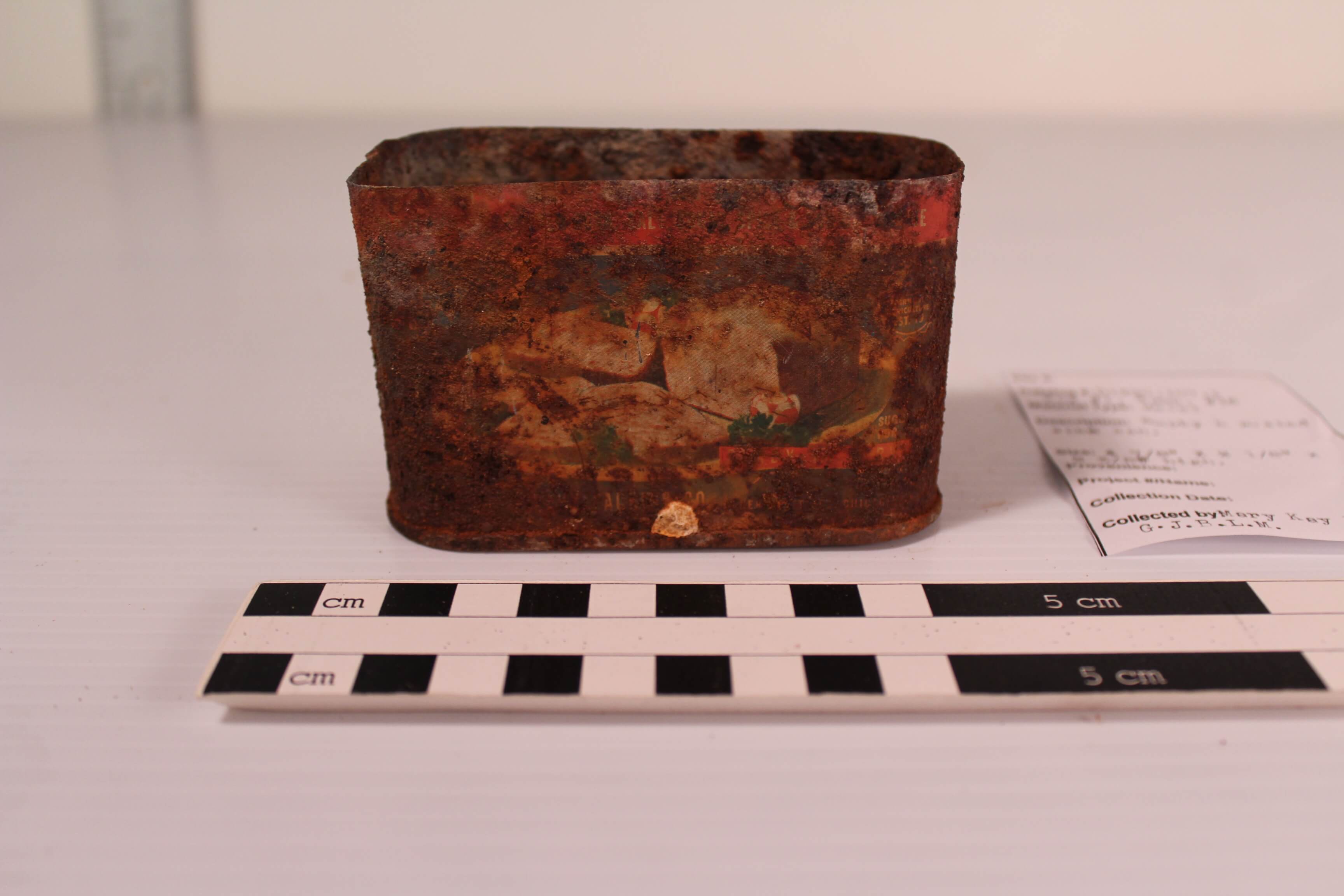

Today at the Calamity Camp site, visitors can see the preserved camp buildings and can explore the camp structures. They stand as a reminder of an important part in Western Colorado history. The Grand JunctionField office of the BLM, the Museum of Western Colorado, and Gateway Canyons Resortare actively working to preserve the site by stabilizing the buildings, and interpreting the story of Calamity Camp to the public. If you visit Calamity Camp, please visit with respect and leave all items in place and take only pictures. Even everyday or seemingly abundant items like tin cans and sandstone cores offer additional information about the people who made this unique historical site their home. When visiting, remember to “Visit with Respect.” Tips on visiting with respect are found at http://www.westerncoloradoheritage.org/stewardship/

We Need Your Help

We need your help to complete the story of Calamity Camp. The Museum of Western Colorado is searching for information, photographs, and people to interview about Calamity Camp and the surrounding areas. Please click here for more information or to contact the Museums of Western Colorado.

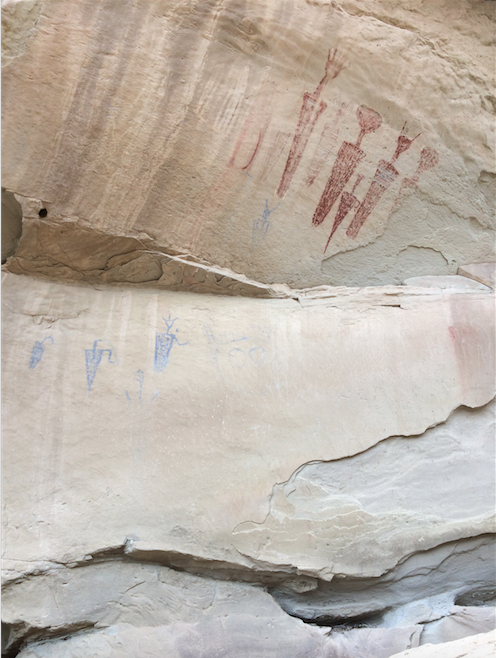

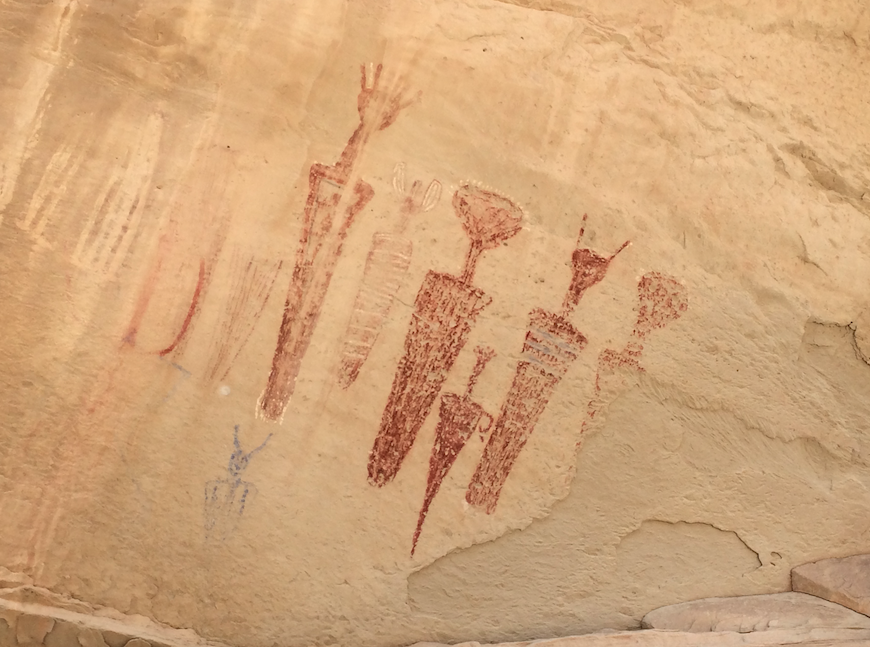

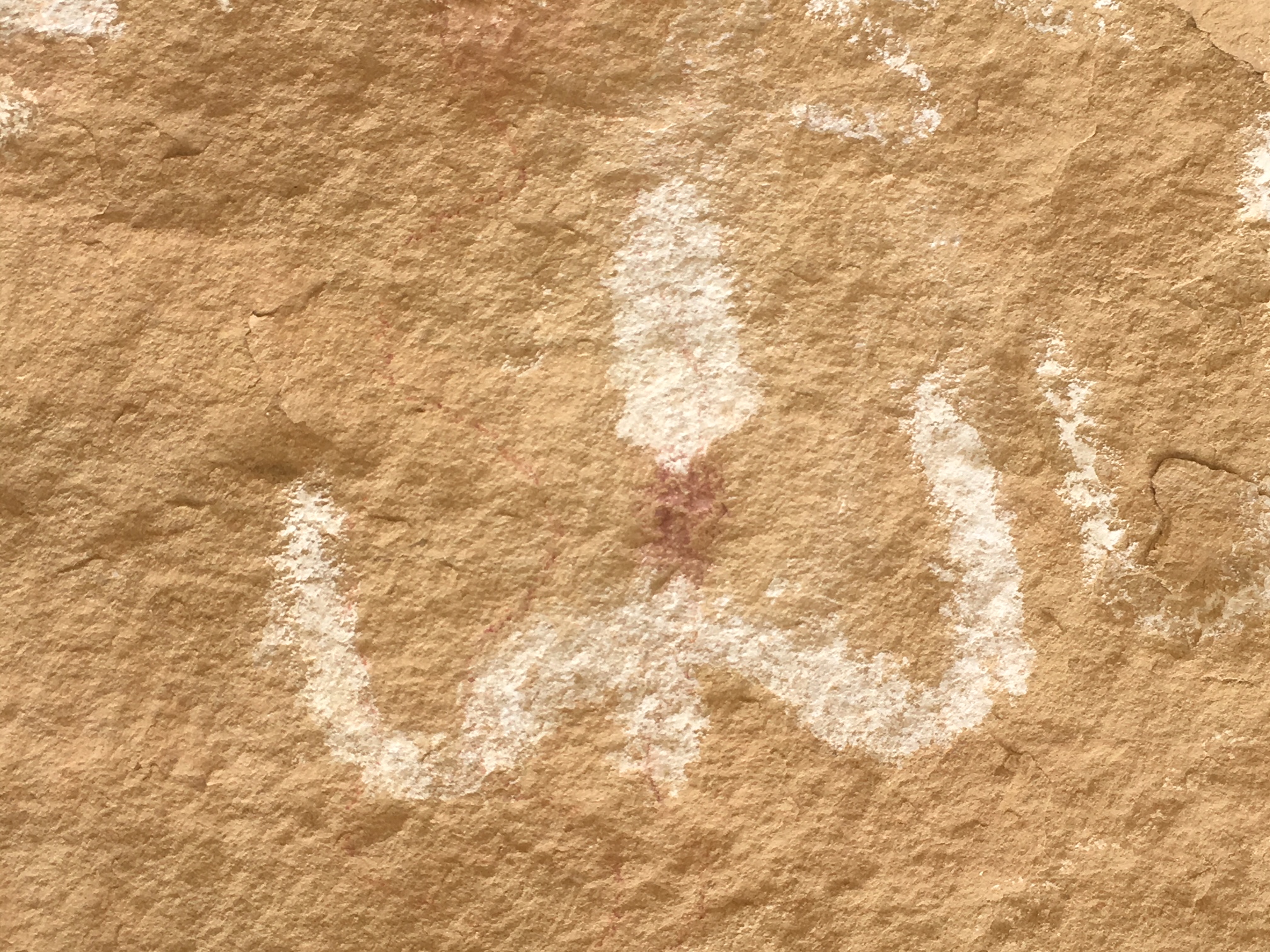

Rock Art – Canyon Pintado

Rock art is one of man’s oldest forms of communication and one of the most universal. Rock art can be found on every continent except for Antarctica and some rock art sites in Europe have been dated as far back as 30,000 years old. By studying the images that our ancestors have left behind, we can get a fascinating and intimate glimpse into our past. The Colorado Plateau is one of the greatest places in the entire world to see and study rock art. The abundance of sandstone cliffs has created thousands of ideal canvases for petroglyphs and rock overhangs have protected painted images for thousands of years.

How is Rock Art Made?

There are several different ways to create rock art. Petroglyphs and pictographs are the two most common types found on the Colorado Plateau.

Petroglyphs are the most common form of rock art. Images are created by pecking and carving into rock by striking the surface with a hard rock and hammerstone. Petroglyphs are commonly found on sandstone cliffs that have a high amount of dark staining known as desert varnish.

Pictographs are images that are painted onto rocks. The pigmentation generally comes from ground minerals and a binding agent such as animal blood or fat or sap is used to hold the paint to the rock surface. Pictographs tend to be found under rock overhangs or caves which have protected the images from the weather.

Rock Art Styles

Each period, each region, and each culture have a unique way to draw figures. There are many different styles that archaeologists have cataloged that have slight twists and variations of their own. However, some common themes are found in each style. Rock art images can easily be broken into four different groups:

Abstract: Abstract images depict things that do not obviously occur in nature. Spirals, wavy lines, and geometric shapes are all examples of abstract images. Each image had a meaning and purpose to their creators. However, this meaning is not completely clear to us today.

Representational: Images that clearly depict something found in nature are representational. Animals, people, footprints, and plants can be clearly identified and are classified as representational.

Anthropomorphs: If an image has human-like qualities such as a torso, head, arms or legs it is an anthropomorph. Some anthropomorphs are very representational with eyes, mouths, headdresses, and jewelry while others are very abstract with elongated torsos or disproportionate limbs.

Zoomorphs: Images that have animal-like qualities are zoomorphs. Like anthropomorphs, zoomorphs can be very realistic or very abstract. Lizards, birds, and sheep are very common on the Colorado Plateau.

Periods

Archaic rock art on the Colorado Plateau is estimated to date from 3000 BC to AD 500 (5,000 years ago to 1,500 years ago). The Archaic covered such a large amount of time and space that several different Archaic rock art styles have been identified. Generally, Archaic rock art has many abstract-geometric shapes and very realistic anthropomorphs.

Barrier Canyon Style rock art (1000 BC to AD 500) spans from the Grand Canyon, across eastern Utah, and into northern Colorado. The biggest indicator of Barrier Canyon is a supernatural feel. Anthropomorphs have broad shoulders and tapering bodies, but details, such as jewelry, tend to be missing. Snakes are very common as are figures with large, hollow eyes.

Fremont rock art (AD 500 to 1300) is found in most of Utah, northwest Colorado and into parts of Arizona, Utah, and Idaho. Anthropomorphs tend to have trapezoidal shaped bodies and some styles pay close attention to face markings, digits, and jewelry. Zoomorphs include snakes and big horn sheep with curving horns. “Shield” figures are also common which are anthropomorphs with large round bodies.

Ancestral Puebloan rock art (AD 500 to 1300) is spread over a vast distance and over a large range of time, with each region having its own variation. Handprints are common in all Ancestral Puebloan styles, as are animal tracks and large quantities of zoomorphs. The flute player figure, commonly called Kokopelli, is featured and abstract symbols are carefully created. Details in animals are vivid and both petroglyphs and pictographs are used.

Ute rock art in the earliest years is very difficult to separate from other rock art styles, but by 1600 unique characteristics can be seen. Early Ute rock art (pre-European contact) depicts men with shields and spears. Late rock art is most easily identified by men on horseback and details on clothing and weapons and modern tools. Bears are also very common in Ute rock art as either the entire animal or bear paws.

While archaeologists can only ask suspected ancestors of the Fremont and Ancestral Puebloan about the meaning of those culture’s rock art, the Ute are still with us today to offer insight.

Rock Art Preservation

While some rock art images on the Colorado Plateau have lasted 3,000 years, this valuable and spiritual resource is in danger. It is now rare to come across a rock art panel that has not been vandalized by graffiti, bullet holes, or have elements completely removed. Please, do your part to protect these cultural treasures.

Visit with respect. Many cultures today see rock art as being just as sacred as it was when it was created.

Do not touch images. The oils on your hands cause damage that cannot be fixed.

Take only pictures. Paper rubbing and latex molds cause irreversible damage.

Respect private property rights.

Leave archaeological clues found near rock art panels in place. Artifacts such as projectiles can help archaeologists better understand and date the age of panels.

Report any vandalism to a local land agency such as the Bureau of Land Management, Forest Service, or Park Service.

Canyon Pintado

One of the most abundant rock art sites in Colorado is Canyon Pintado. The Canyon Pintado National Historic District covers over 16,000 acres of public land along 15 miles of State Highway 139 between Fruita and Rangely. There are hundreds of archaeological sites along the canyon from the Fremont and Ute people. The BLM manages the area and has built trails and signs along the way so that people can visit and learn about the area and its history. Canyon Pintado (Spanish for “Painted Canyon”) was named by Fathers Dominguez and Escalante in 1776. Their trip took them through the canyon and they were the first Europeans to see the ancient Native American rock art as they traveled through the Douglas Creek Valley.

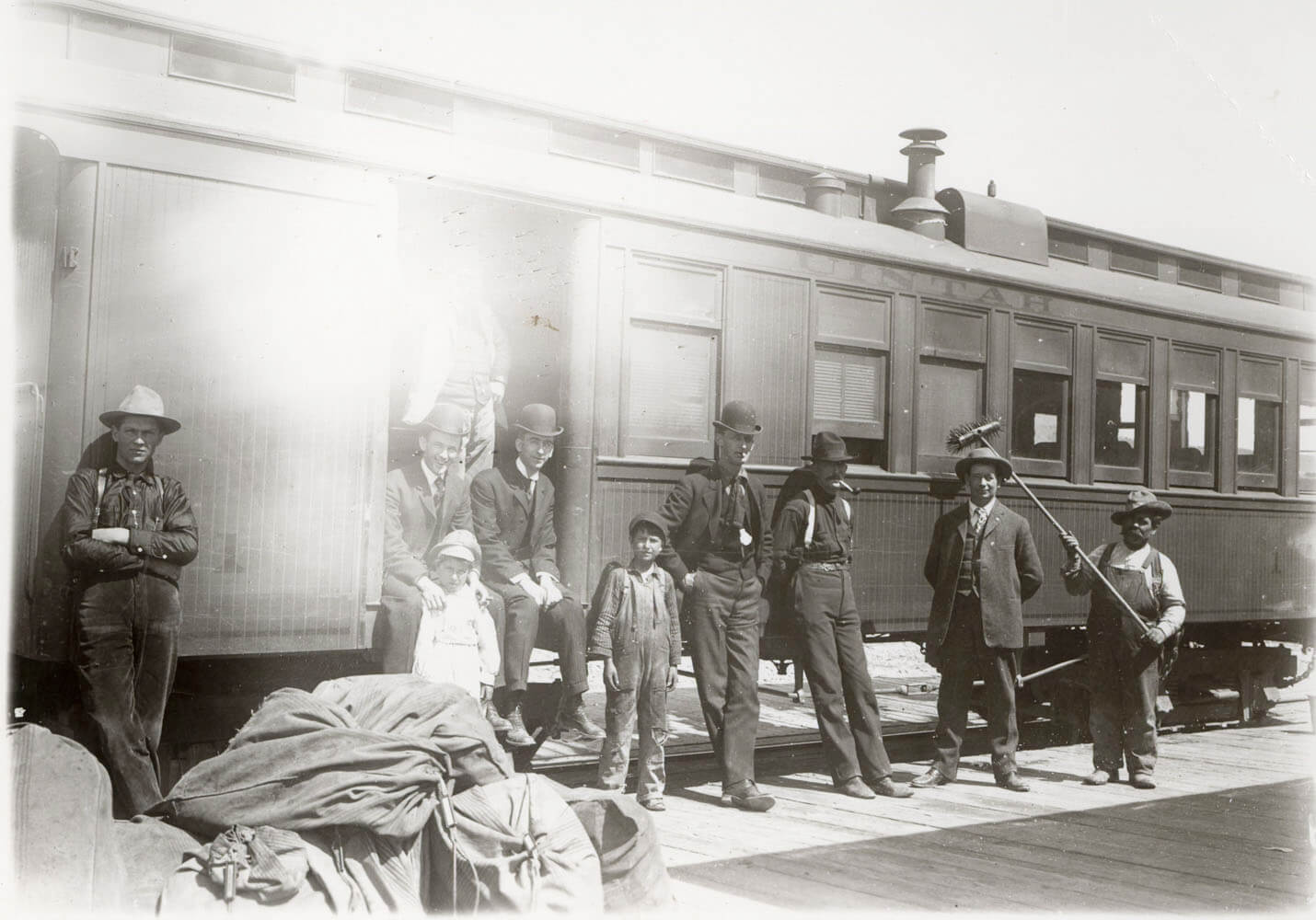

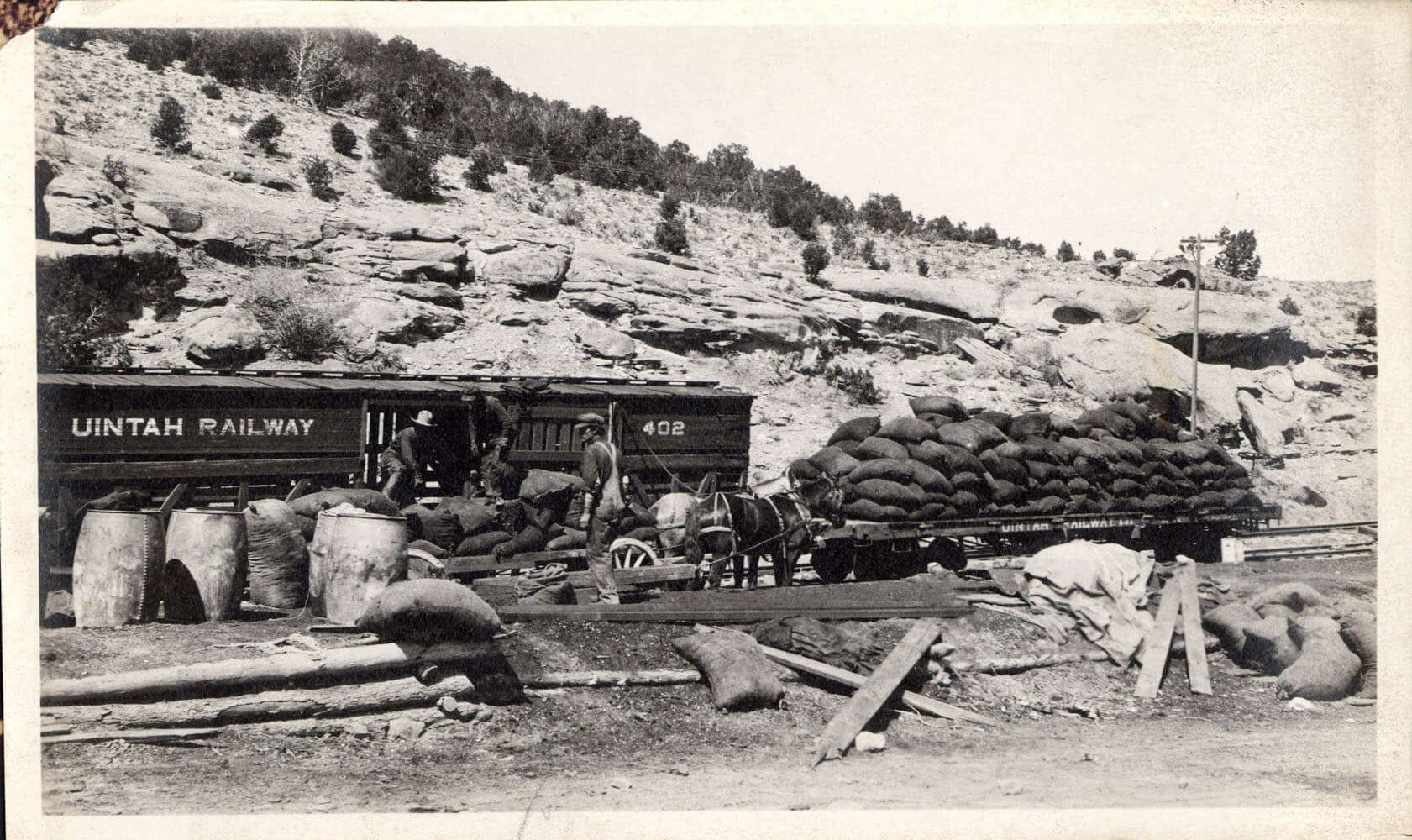

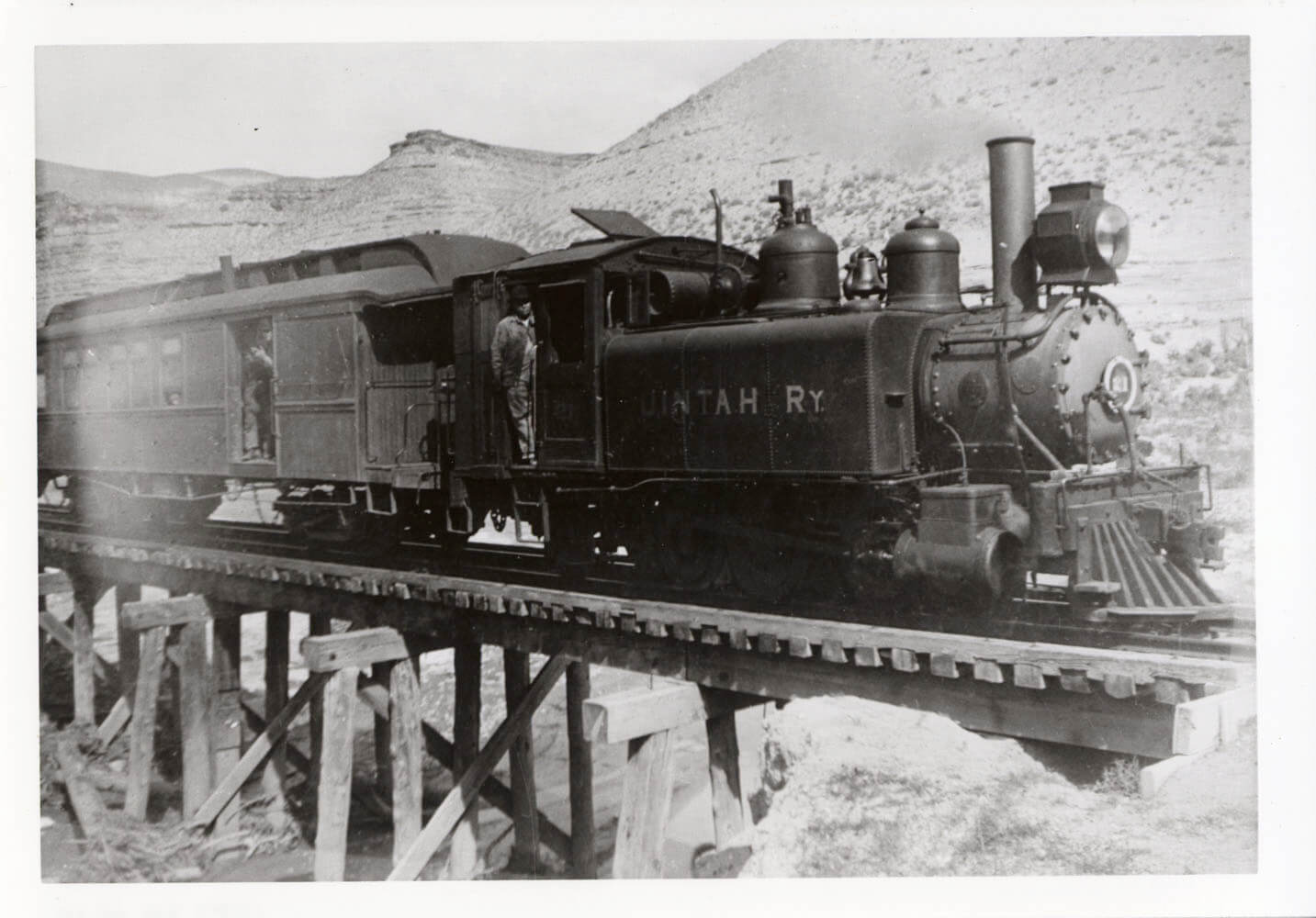

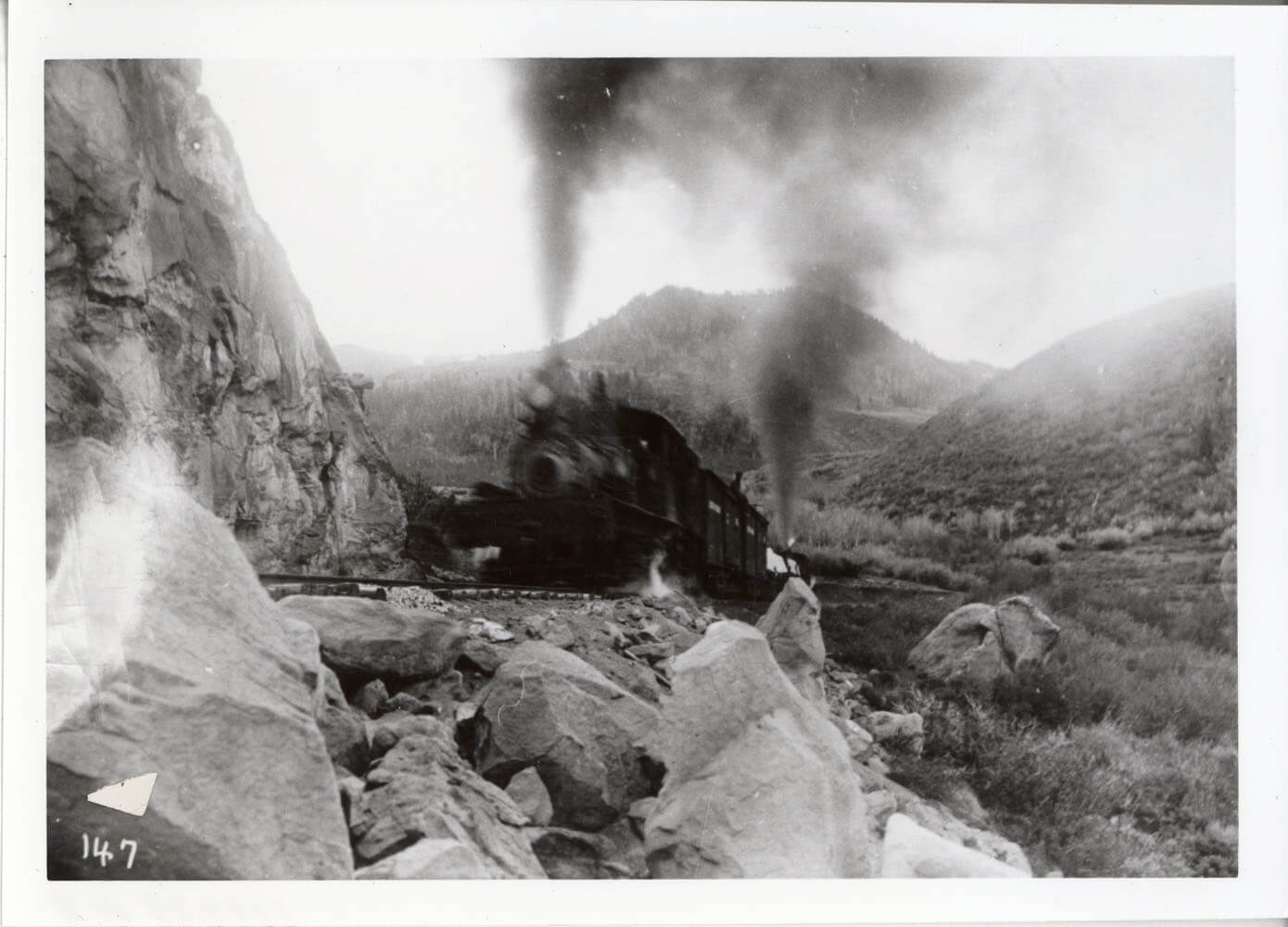

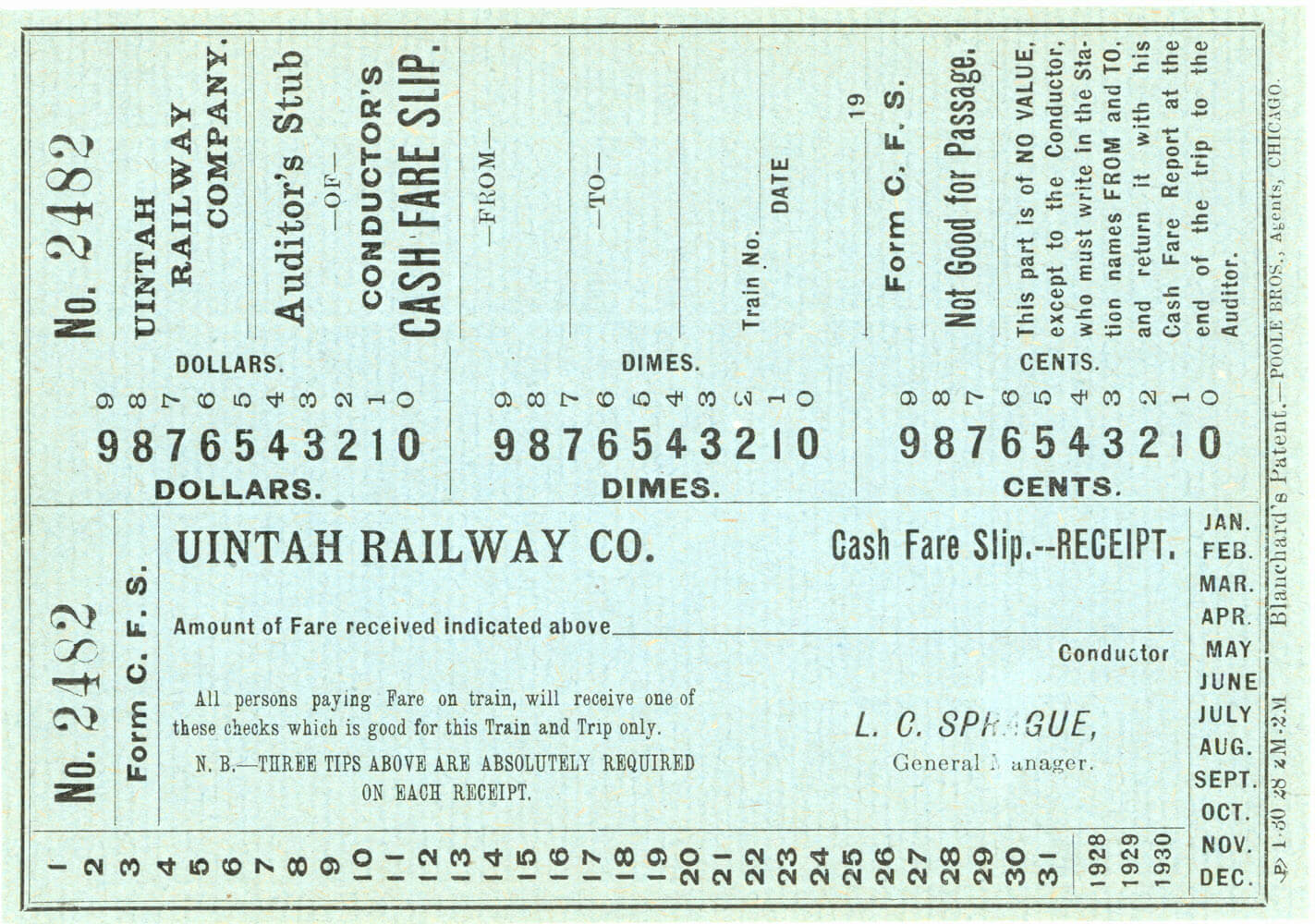

Uintah Railroad

In 1904 the Gilson Asphalt Company founded the Uintah Railway. The goal of the Uintah was to reach the new gilsonite mines near the towns of Dragon and Bonanza, in Utah. The Uintah built north out of the newly founded town of Mack, CO in part founded by the railroad. The Uintah was built narrow gauge, and reused some of the abandoned grade of the old Denver & Rio Grande Western. The Uintah climbed the Bookcliff mountains over Baxter pass, 8437 ft.in elevation, which was the steepest, most crooked grade alignment in North America. The grades were a staggering 7.5 percent with 66-degree curves. The Uintah utilized geared steam locomotives called Shays and had 2 unique articulated tank steam locomotives especially built for the steep climb and sharp curves.

The Uintah Railway ceased operations in 1939 when it was decided to switch the hauling of gilsonite to trucks. The right of way was turned into a road and the equipment was sold off or scrapped. Many of the freight cars were sold to local ranchers, who used them as storage sheds or chicken coops.

Starting in the 1980s the Rio Grande Chapter of the National Railroad Historical Society, inconjunction with the Museum of Western CO, began searching for and acquiring old Uintah freight cars. The car types collected range from a flat car to a caboose. The crown jewel of the collection is caboose # 3 which was found in desperate condition with no interior and was almost lost, but it has been completely restored. The cars are open to visitors during special events at Cross Orchards.

Another piece of Uintah history that was saved was the Whiskey Creek Trestle in Rio Blanco county 25 miles southwest of Rangely, CO . When the Uintah was abandoned,the right of way was converted into a county road. Most of the trestles were retained for the new dirt road and were replanked to carry automobile traffic. Over the years, the road was realigned, and the trestles were bypassed due to their extreme age and or poor condition. The Whiskey Creek trestle was circumvented in the 1960s, when a large culvert was installed in the creek bed and the road was rerouted. The trestle sat abandoned from that point on. In the late 1970s, the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) recognized that since it was the last trestle of the Uintah,itshould be declared a historic site.It was nominated to the National Register of Historic Places in 1980. An interpretive sign was placed at the trestle, indicating its history and purpose.

The Journal of the Western Slope was published quarterly by two student organizations at Mesa State College: the Mesa State College Historical Society and the AlphaGamma-Epsilon Chapter of Phi Alpha Theta. The journal’s primary goal was to preserve and record the Colorado Western Slope’s history. The first issue was published Winter 1986 and the last in Winter 2002.

Access the collection here.